(Transcript of the podcast)

(Transcript of the podcast)

A diving into environment variables.

What are environment variables

What are environment variables?

A set of dynamic values, helper or configuration values, that can affect the

way a process runs.

Usually it’s the process that queries those values,

they are part of its “environment” and consequently the name.

They are there so that the process can know the suitable values of the system

it’s running on.

They are metadata, so to say.

For example, the temporary location to store temporary files, or the home

directory.

This defintion is vague, the implementation could be done in a lot of ways. What’s really an environment variable… Well, this isn’t clear. Are those environment variables respected, forced? Also, this isn’t a clear thing.

Historic

They were introduced in their modern form in 1979 with Version 7 Unix,

so are included in all Unix operating system flavors and variants from

that point onward including Linux and OS X.

They all use the standardized format of colon separated values that can be

queries system wide.

Details - The Life cycle - At which point they are loaded, and where, by who

Let’s dig into the details. In all Unix and Unix-like systems, each process has its own separate set of environment variables. By default, when a process is created, it inherits a duplicate environment of its parent process, except for explicit changes made by the parent when it creates the child. At the API level, these changes must be done between running fork and exec.

After that, the values the running program access are static. Anything changed in a script or compiled program will only affect that process and possibly child processes. The parent process and any unrelated processes will not be affected.

On Linux:

Each process stores their environment in the /proc/$PID/environ

file. This file contained each key value pair delimited by a nul character

(\x0). A more human-readable format can be obtained with sed, e.g. sed

's:\x0:\n:g' /proc/$PID/environ.

Take a look:

< /proc/self/environMore generally the env variables are passed to the program via the

execve, the last argument is an array of key value. (see man execve

and man environ). However, note that the size of this array is

generally limited.

On a lower level, the process manages the variables internally in the

char **__environ array, following the standard POSIX spec.

(For more info on the system calls, see man (7) environ).

There are numerous files that are read, sequentially, to fill those environment

variables.

There are also command line facilities, usually implemented by the shell,

to access the variable list and to change them.

We said that it’s sequential, so there’s an order to this.

Let’s examine the process in which environment variables are set.

- System

- Login

- Session & Shell specific

- Temporary - pseudo-environment variables

- Before Execution

The idea is simple, the newest file read will override the previous one. Let’s answer first, “read by whom?”. It’s read by the shell or program.

System set environment variables

The system set environment variables, those are the ones inherited by all other processes started on the system. The ones initialized at the system startup.

Example:

/etc/profileand/etc/environment/etc/profile.d/*

/etc/profile initializes variables for login shells only. It does,

however, run scripts and can be used by all Bourne shell compatible

shells.

/etc/environment is used by the PAM-env module and is agnostic to

login/non-login, interactive/non-interactive and also Bash/non-Bash,

so scripting or glob expansion cannot be used. The file only accepts

variable=value pairs.

Login

/etc/profile and pam_env.conf

See man 8 pam_env

Session & Shell specific

Augmenting the global Environment variables. Be it session-wide vs system-wide

/etc/yourshell.rc #more or less global too

~/.profile

~/.yourshellrc

~/.pam_environment

.xinitrc #if you are doing it for the GUI - subsection (per graphical session)/etc/bash.bashrc initializes variables for interactive shells only. It

also runs scripts but (as its name implies) is Bash specific.

Temporary - pseudo-environment variables

The temporary pseudo-environment variables, are on the spot, set by the shell. Any shell script can be used to set the environment variables.

So what’s the difference between persistent vs non-persistent.

True environment variables vs pseudo-environment variables. Stored

staticaly in the environment vs queried from the environmnent but not

really available.

In Unix shells, variables may be assigned without the export keyword. Variables defined in this way are displayed by the set command, but are not true environment variables, as they are stored only by the shell and not recognized by the kernel. The printenv command will not display them, and child processes do not inherit them.

Before execution

Between fork and exec.

Most common ones

Let’s note before starting the list of most common ones that,

In Unix and Unix-like systems, the names of environment variables are

case-sensitive.

It is also a common practice to name all environment variables with only

English capital letters and underscore signs.

Let’s dig some common ones.

PATH

/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

When you type a command to run, the system looks for it in the directories

specified by PATH in the order specified

MANPATH

/usr/share/man:/usr/local/man

List of directories for the system to search manual pages in

HOME

PWD

Current working dir

DISPLAY

Current display

LD_LIBRARY_PATH and LD_PRELOAD

This is where the dynamic linker will load code from LD_LIBRARY_PATH and

LD_PRELOAD.

This is where the runtime libraries are in addition to the ones hard-defined

by ld and the ld conf.

LANG, LC_ALL, and LC_ ... - TZ

These are Locale setting variables. The following environment variables determine the locale-related behaviour of the systems such as the language of displayed messages and the way times and dates are presented.

RANDOM

Generates a random integer between 0 and 32,767 each time it is referenced.

PS1 and PS2

(default prompt, and waiting prompt)

TERM

The terminal type.

Usually the type of terminal you are using is automatically configured

by either the login or getty programs. Sometimes, the autoconfiguration

process guesses your terminal incorrectly.

If your terminal is set incorrectly, the output of commands might look

strange, or you might not be able to interact with the shell properly.

To make sure that this is not the case, most users set their terminal

to the lowest common denominator.

TMPDIR

Usually, /var/tmp

The directory used for temporary file creation by several programs

Preferred application variables

(this could be a whole podcast)

PAGER vs VISUAL

PAGER

Example: /usr/bin/less.

The name of the utility used to display long text by commands such as man.

EDITOR

Example: /usr/bin/nano.

The name of the user’s preferred text editor. Used by programs such as

the mutt mail client and sudoedit.

VISUAL

Example: /usr/bin/gedit.

Similar to the “EDITOR” environment variable, applications typically

try the value in this variable first before falling back to “EDITOR”

if it isn’t set.

- PAGER

The pager called by man and other such programs when you tell them to view a file.

- VISUAL

This variable is used to specify the “visual” - screen-oriented - editor. Generally you will want to set it to the same value as the EDITOR variable.

- EDITOR

Originally EDITOR would have be set to ed (a line-based editor) and VISUAL would’ve been set to vi (a screen-based editor).

These days, you’re unlikely to ever find yourself using a teletype as your terminal, so there is no need to choose different editors for the two. Nevertheless, it is useful to have both set. Many programs, including less and crontab, will invoke VISUAL to edit a file, falling back to EDITOR if VISUAL is not set - but others invoke EDITOR directly.

BROWSER

The name of the user’s preferred web browser. This variable is arguably less common than the rest.

Must know

It’s enough blahblahblah, we want to know some practical things. There are other things to know other than the files to set the variables in, there utilities ?

The thing we’re mentioning here are happening at the session level. Most shell will let you interface with the environment variables as if they were local shell variables. By putting the dollar sign in front of the variable you want to check you can use it as you would use a normal variable but accessible everywhere inside the script. For instance, right in your shell you can do:

echo $HOMEAnd it’ll print the value of the HOME. You can also change them like you would change a normal shell variable however it’s wiser to use the other utilities your shell offers for this.

Many shells distinguish between shell variables and environment variables. A shell variable is defined by the set command and deleted by the unset command.

% set name=valueSome shell simply allow VAR=VALUE

Environment variables are set by the setenv command, and displayed by the printenv or env commands, or by the echo command as individual shell variables are. Some other shell use the export command. The formats of the commands are (note the difference between set and setenv):

% setenv [NAME value]

% unsetenv NAME

or export NAME=<value>

or export NAME=With nothing on the right to unset it.

You can call the setenv command, printenv, or env or export without argument and it’ll print the list of all the values already set. The commands that will work depends on the shell you are using.

VARIABLE=value #

export VARIABLE # for Bourne and related shells

export VARIABLE=value # for ksh, bash, and related shells

setenv VARIABLE value # for csh and related shellsTips & Tricks & Relevant Tools & Commands

VARIABLE=value # shell variableWe can specify shell variables in the front, before calling a program, and depending on the shell it’ll be considered as a real environment variable for that process.

VARIABLE=value program_name [arguments] ~ > cat t.pl

use Env qw(PATH HOME TERM);

use strict;

use warnings;

print $HOME;

~ > HOME=test perl t.pl

test%

~ > echo $HOME

/home/raptorThe env command line utility is a shell command for Unix and Unix-like

operating systems. It is used to either print a list of environment

variables or run another utility in an altered environment without having

to modify the currently existing environment.

env is commonly used in shell scripts to launch the correct interpreter.

You see it in the hashbang line of scripts allowing the interpreter to be looked up via PATH. It’s possible to specify the interpreter without env but you’ll have to give the full path and this is highly system dependent while the env command alleviate this issue, it makes it more portable. Calling env without arguments will print all the environment variables. Actually any of those commands we talked about has that behavior.

Now a little tricks, we said we could look the list of environment of a process on Linux using the /proc but there’s another nifty way using ps.

ps e -p <PID>More

Now let’s talk about more philosophical stuffs beyond the scope of the article.

/etc/skel is the skeleton used for the home of the new users that are going to

be created on the machine.

If you want to set some session variables for all new users you may want to put

it there.

When changing user using su.

the -l argument is the same as a - without anything else (dash).

The -l simulate a full login, which means that all the current environment

is discarded except for HOME, SHELL, PATH, TERM, and USER.

So in sum:

su - will reset the environment,

otherwise it’ll keep the current one.

Some critics warn against overuse of environment variables, because of differences between shell languages, that they are ephemeral and easy to overlook, are specific to a user and not to a program. The recommended alternative is configuration files.

Default application:

Programs coming up with their own way of doing things, like .Xresources

For example the default application… it’s a bit messy

Everyone wants a piece of the cake

Reason: The relation between environment variables and the above discussion on MIME types is not immediate. Setting BROWSER e.a, while also related to default applications, is a different approach entirely. (Discussed in another podcast: Default applications)

References:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environment_variable

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Env

- http://sc.tamu.edu/help/general/unix/vars.html

- http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/hostunx/61879/HTML/default/defenv.htm

- http://stackoverflow.com/questions/1641477/how-to-set-environment-variable-for-everyone-under-my-linux-system

- https://kb.iu.edu/d/acmq

- http://www.tutorialspoint.com/unix/unix-environment.htm

- http://www.cyberciti.biz/faq/set-environment-variable-unix/

- https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Guide_to_Unix/Environment_Variables

- http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/117467/how-to-permanently-set-environmental-variables

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Environment_variables

- https://help.ubuntu.com/community/EnvironmentVariables

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Default_applications

- http://refspecs.linux-foundation.org/LSB_4.0.0/LSB-Core-generic/LSB-Core-generic/baselib---environ.html

Attributions

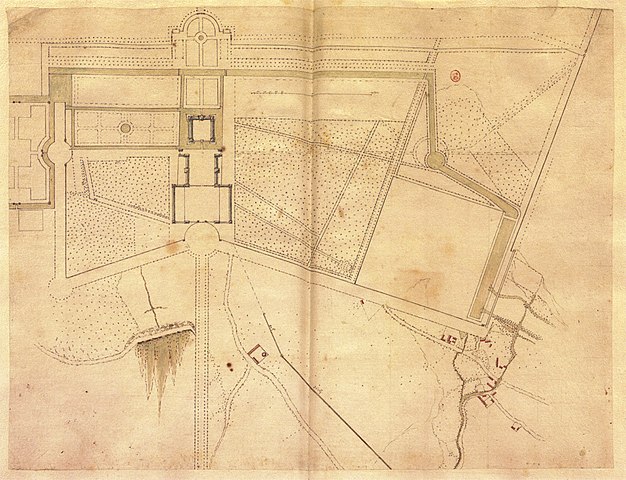

Attributed to Jacques Lemercier / Public domain

If you want to have a more in depth discussion I'm always available by email or irc.

We can discuss and argue about what you like and dislike, about new ideas to consider, opinions, etc..

If you don't feel like "having a discussion" or are intimidated by emails

then you can simply say something small in the comment sections below

and/or share it with your friends.