(Transcript of the podcast)

(Transcript of the podcast)

Intro

Understanding how the fonts work on Unix isn’t simple. I had never thought when starting this research that this field was this deep. Not only is it overwhelming, but the information around the subject is also not easily digestable.

The last two weeks I’ve been researching this and in this podcast you’ll barely find but the essential. It’s still skimming the surface of the topic. If I explain something in a wrong manner, be sure to correct me in the extended podcast discussion thread.

The people that truly understand the full font stack can be counted on one’s hand, I’d like to salute those true heroes. They deserve respect. And if they had an anthem I would’ve played it at the beginning of this episode.

So yes, we’re going to discuss fonts.

What are fonts

Text is made up of sentences and sentences are made up of words, which are made of characters. Written text is our primary mean of communication in computers, and we need a way to represent this on our machine and that’s what fonts are.

When X11 clients or more generally anything wants to draw text on the screen they use fonts files, which are files that contain the set of glyphs, characters, or symbols, or numerals, and rules that are used to know how to draw that font.

Let’s think

Let’s first stop and think for a moment, how would you write a software that draws text on the screen? A benign algorithm would go like this:

- Have a file with the list of characters and their pixel representation.

- Place the pen to the cursor position.

- Load the glyph image.

- Translate the glyph to the origin of the pen position.

- Render the glyph to the target device.

- Increment the pen position by the glyph’s advance width (in pixels).

- Start over again at step 3.

However, it’s not as simple as that.

What about right to left writing. What about languages that need to

reshape their characters differently depending on what it’s followed

or preceded by. What about spacing between letters that also varies.

What about making the text clearer instead of blocky by only fitting

the pixel space. What about resizing the text size?

So many ifs.

Fonts in the TTY

The method of laying text on the screen we just mentioned is not far

from the truth when it comes to TTYs. The virtual console is handled by

the console driver, and it’s that driver that has the role of drawing

the text.

Configuring those drivers differs between the different type of Unix-like OS.

FreeBSD for example comes with no fonts in the kernel but loads the default font from the console driver or vt or syscons while Linux, netbsd, and openbsd have a default fonts inside their kernels.

In most Unix-like OS Those fonts can be changed through configurations. Generically the process unfolds like this:

There’s a keymaps for the console that connects the keyboard layout

currently configured with the keypressed.

For instance on Linux that keymaps is changed in /usr/share/kbd/keymaps/.

At this point we can know which character is requested.

Now we have to get what we want to display from the font structure or file. The format of the console fonts are just hex values for the pixel representation of every character. They are fixed in size usually 8x16 pixels and monospaced, which makes them very simple. More or less literal bitmap representations of characters. Ok, so we got a pixel representation of our character, let’s display it.

To do that we have to use the video graphics array framebuffer, the

VGA framebuffer, which is a standard working on virtually all post-90s

graphic cards that let you directly display things on the screen. But

those also work on CGA, EGA, MDA.

However, there’s a condition here, the console fonts are limited to

256 glyphs and if they want to double to 512 for unicode fonts they need to

reduce the colors used from 16 to 8, the 8 other colors are originally

used to display brighter versions of the first 8, so that the extra bits

are used for the extra characters association.

This translation is encoded inside the unicode font file in a translation

table called the unimap.

Once that’s all set the console can send those bits to the framebuffer,

and they are displayed, the position of drawing then moves where the

cursor is.

The text buffer is a part of VGA memory which describes the content of a text screen in terms of code points and character attributes.

This is sort of similar to our first guess as to how a character would be displayed on the screen, just a notch more difficult and constrained.

The constraint of 512 glyphs can be omitted through a framebuffer translation layer, but we won’t discuss it here.

Let’s discuss font extensions and formats in the console. As far as the BSDs goes, it highly depends on which flavor you are using.

- For Open and Net BSD the font format is wscons. Hardcoded in the kernel

- For Linux the format supported are psf (PC Screen Fonts) and psfu for

unicode fonts.

Located in

/usr/share/consolefonts - For FreeBSD the font supported depend on the console driver:

- for the syscons the format is the .fnt

located in

/usr/share/syscons/fonts/*.fonts - for the vt aka Newcons the format supported is the hex fonts, note that this supports unicode while the latter doesn’t The fonts are set manually, not necessarily located anywhere.

- for the syscons the format is the .fnt

located in

The common thing between all those formats is that they are bitmaps and

thus easily editable and convertable from one to another.

There are tools to convert from bdf format to wscons. From bdf to

HEX format. From bdf to sfntf (The same format container used for TTF

and OTF), such as fonttosfnt. From PCF to BSD, such as pcftobdf.

Many psftools, such as otf2bdf. Refer to this thread on the nixers

forums

to know how to convert PCF/BDF fonts to be compatible with the latest

version of Pango/HarfBuzz.

You can even show those bitmaps directly on the screen using a tool

called raw psf.

And if you were wondering, BDF stands for Glyph Bitmap Distribution

Format, which is exactly what we want, another bitmap font format.

Now the specific configuration and how to set the fonts and keyboard

translation are specific to the Unix-flavor and I won’t list the commands

themselves. You can easily refer to the show notes for that.

For instance showconsolefont on Linux display a preview of all the

glyphs in the current font.

Unicode what? locale?

We rather often hear about locales and unicode that we need to set when installing a new Unix-like OS on a machine. What are those? Do they have a relation to fonts? Let’s read a nice definition that clarifies this:

A locale is a set of language and cultural rules. These cover aspects such as language for messages, different character sets, lexicographic conventions, and so on. A program needs to be able to determine its locale and act accordingly to be portable to different cultures.

So locale could be used to specify anything that varies from one culture to another and whichever program can choose to respect them. So what does this have to do with anything we’ve said so far?

Well, there’s a relation to the keyboard translation table, remember

that first part that translates whatever key you press into characters.

This is dependent on culture, for instance if you have an AZERTY keyboard

you need to set that in the locale, the VC Keymap.

But it doesn’t stop there, text is language and language varies by locale.

On a lower level, locale works by changing the behavior of many functions

inside the C library, for instance isupper, toupper, strftime, etc.

You could disply the time in a 24h format instead of the 12h one.

All change according to your preferences.

It also changes the default language for output of many programs, for

example manpages.

There was a time when one would need to input, render, print, search, spell-check, all in one language at a time. A single character set for every locale. Now with the adoption of Unicode, 8 bits or multibytes instead of 7bits, as the canonical character set we don’t have to do that anymore. It’s all languages all the time.

The command you have to remember about locale is locale.

So in conclusion, locales don’t really have anything directly related to fonts.

Different types of font, extensions

When moving a layer up, in the graphical land there’s more room for flexibility with fonts.

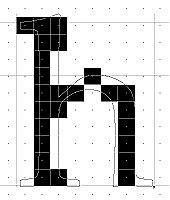

There are two generic categories of font formats, either bitmap fonts,

just like the ones we discussed earlier, consisting of a matrix of

dots or pixels representing each glyph, or outline or vector fonts,

consisting of Bézier curves, drawing instructions, and mathematical

formulae to describe each glyph, making them scalable.

For instance the extensions we mentioned earlier pcf, bdf, wscons,

etc. Are bitmap formats while extensions like otf, ttf, and pfa are

outline formats.

There are many font extensions which follow different formats falling in either one of the category, bitmap or outline, you can find a list of them in a link in the show notes.

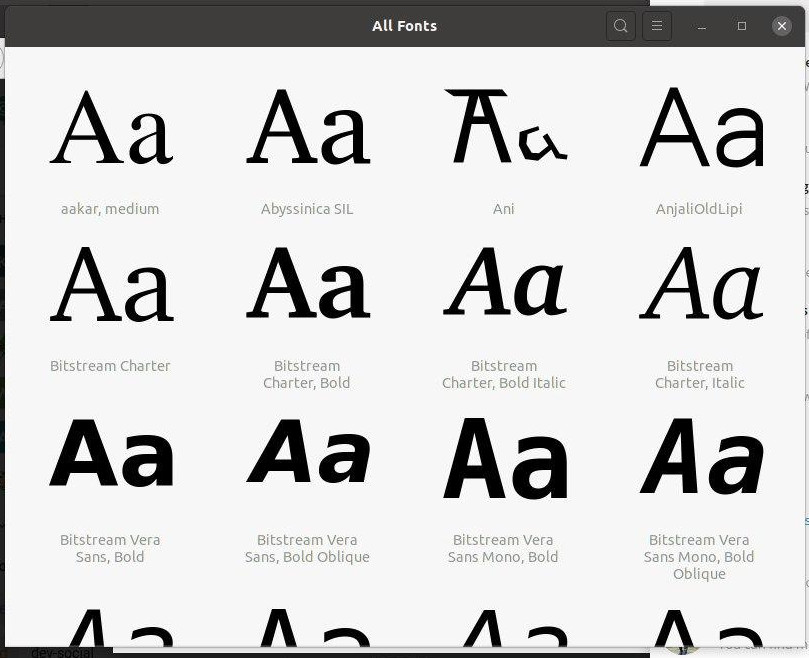

A font itself is a family or also called a typeface, for instance the

font Vera Sans is a typeface. The typeface can divide up into different

versions of that font, one could be bold, another italic, another serif,

another monospace, etc.

We’ll come back later to discuss what is inside some of those files and

how to manage them.

Generic overview

We’ve seen how text is layed on the screen when using the TTY but what about the graphical environment, how is it rendered there? Starting from bottom up here’s how it goes:

-

At the complete bottom of the stack the display server receives some shapes to draw.

-

A library is used to send the appropriate glyphs to the display server doing some adjustments before sending it when appropriate.

-

A library is used to load the font from the font file and rasterize it, that is converting it to a bitmap if it’s not already. It can also add hinting and anti-aliasing which we’ll discuss in a bit.

-

A font layout and shaping engine keeping track of where to lay down everything and how, figuring out the complex rules for the font and language in use. It’s a sort of state machine for the glyphs.

-

A software responsible for managing the fonts, configuring what kind of adjustments need to be made on them, knowing their location and searching for them.

-

A software requesting some text to be drawn on the screen.

Don’t worry about most of the details here, just try to grasp that there are different softwares layed upon each others doing different tasks. We’re going to name the different softwares later on and explain in depth what they do but you’ll need that little overview to make it easier to understand.

The problem with fonts on screens

Ok, so that’s a very generic overview of how things should happen to draw text in a graphical environment. Before continuing, we need to take a little detour to explain something. We went into the details of how to display bitmap fonts but what about vector/outline fonts, which most of the graphical fonts are?

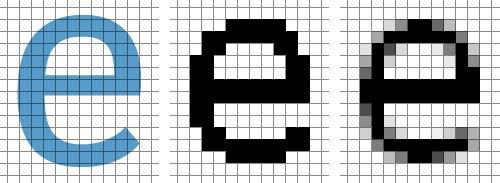

The process of converting text from a vector description to a raster or bitmap description is called font rasterization. This also involves doing some graphical operations to make the text easier to read, to optimize rendering it, like anti-aliasing and hinting. But why do we need that? And what does hinting and anti-aliasing do?

The problem emerges from the fact that we’re using pixelized screens,

it all comes down to the resolution of that screen, the number of dots

per inch, DPI.

Fonts are not mesured in dpi however, they are mesured using another

metric, the points, so that irrespective of the output device they’ll

keep the same physical dimension.

And thus, it would mean that the higher the DPI the cleaner the drawing

of that glyph would appear and the lower the DPI the more distorted the

glyph would appear.

It’s not unusual for printers to have a DPI going from 300 to 500 while

most of today’s LCD screens have a DPI around 96, which is insufficient

for accurate rasterization.

And because all problems need a solution, we certainly have one or many.

Let’s discuss three of them.

- Font Hinting

Font hinting aka grid fitting is a technique that modifies the shape of

the glyph so that its ensured to line up with the rasterization grid,

in the case of LCD it means lining it up with the pixels.

That gives a more consistent text than the un-hinted counterpart however

this consistency comes at the price of accuracy, hinted text doesn’t

have the same shape that was intended by the font creator.

However, hinting is a great way to make small text readable on low

resolution devices.

There are many “levels” of hinting and hinting can happen at different layers in the font rendering stack. For example the hinting rules can be embedded inside the font file or it can be automatically done by some library along the way without any rules implied.

N.B.: Until May 2010 TrueType bytecode hinting was patent encumbered by Apple.

- Anti-aliasing

Anti-aliasing is a technique that uses the property of a pixels being able

to display shades of colors, instead of full-blown red or green or blue,

to create a blur signal around the glyph to reduce its maximal frequency.

In layman’s term anti-aliasing means to avoid aliasing, which in the

signal processing world means the effect that causes different signals

to become indistinguishable, which in our case means that because we

have low dpi many details are contained within a single pixel and thus

are indistinguishable. And to do that we create a ghostly effect that

creates back the details.

This does a good job at preserving the shape and aspect of the glyph but at the cost of clarity because anti-aliased text is made of much lower contrast. As opposed to hinting, anti-aliasing can’t be embedded in fonts and is usually done at another layer.

- Combining Anti-aliasing With Hinting

Now the question is: Can we combine those and would we get better results? The answer is that it depends on the order of how they are applied.

If hinting is done on an already anti-aliased text it’ll consider the

ghost applied around the glyph and also apply hinting to it, which might

deform the text even more.

This is particularly an issue if the hinting is embedded inside the

font file and is applied directly by the layer that is responsible for

the reading and handling the font files.

The solution to this is to apply hinting and anti-alias at another

layer and not in the font and only to use slight hinting and not

aggressive hinting.

- Sub-pixel Rendering

![]()

Sub-pixel rendering is a technique or more of a hack that uses a property of LCD or OLED screen pixels to make it appear as if the resolution of the display is higher than what it is.

A pixel is composed of multiple sub pixels, it might be 3 sub-pixels, one for red, one for green, one for blue. Those pixels are arranged and layed in a fixed order for the same screen, so for instance a pixel has the red, green, blue sub-pixels layed out horizontally in that order from left to right.

The way sub-pixel rendering increases the resolution of the screen is by

playing around with those sub-pixels in a way similar to anti-aliasing

but at a smaller level combining this with the fact that our eyes have

difficulties finding differences between the sub-pixels colors when they

are using small intensities.

Imagine it as considering sub-pixels as if they were whole pixels,

though it’s not really that.

There’s an excellent link in the show notes showing in details how this work if you want more information on that topic.

There are two drawbacks.

The first one is that it only works with displays that use technology

similar to pixels.

The second drawback is that sometimes you can notice the colors of the

subpixels with your eyes. That is an effect called color fringing,

seeing the sub-pixel color on the fringe of the glyph. It is due to

bad filtering such as sub-pixel rendering not regulating correctly

the intensity of the sub-pixels. It can be countered by using a better

filtering to normalise the difference between adjacent sub-pixels.

N.B.: Microsoft has several patents on subpixel rendering technology and thus it’s disabled by default in some free software rendering tech such as FreeType.

- Subjectivity of fonts

So those are techniques to make or try to make the font look better. But “better” is a subjective word.

One relevant example is when Apple first released their Safari browser for Windows in 2007. While doing that they bundled with the browser their font rasteriser which gave the opportunity for people to judge which approach font rasterizing they found better. Multiple bloggers commented on this subject, some liking it, while most didn’t. But overall there was no real way of knowing which one was better suited at its job. Both did what they were intended to do. Windows users prefer Microsoft’s system and Apple users prefer Apple’s system.

The moral of the story is that consistency between font rendering within one OS is the key.

The Stack

Now that we know the challenges of font rasterization we can finally discuss the real software stack that sits on a free Unix system.

We’ll discard Apple but you can still read about it in the show notes.

Let’s just say that It uses Quartz for rendering on the screen, it’s

the graphic engine, and take the approach of not forcing glyphs into

exact pixel position, so no hinting at all, not even the hinting found

inside the font file itself. Instead, it uses a combination of anti-alias,

sub-pixel rendering, and sub-pixel positioning. The rasterization and

layout takes place inside the AAT, Apple Advanced Typography.

That’s all we’ll say.

So on other Unix-like OS, what’s the stack?

The answer is somewhat non-binary, it’s not straight forward because as

with everything in the free Unix world there are many options to achieve

the same goal.

The result is a collection of separate modules sitting on top of each

other, each influencing the rasterization process.

At the very bottom of the stack we have the graphical stuffs, the things that handle directly drawing on the screen. This is usually the display server, X11 or a Wayland compositor. It receives the shapes of the glyph in the form of raw-pixels from somewhere and draws them, that’s its job. X11 has the X render extension that provides basic support for caching client side rendered glyphs shapes, so that they aren’t recomputed.

Now moving up we get the piece responsible for interacting with the

display server, the piece that uploads the image that we want to render.

Some times ago this piece was directly incorporated inside X11 and so

the RENDER extension we just talked about didn’t need to exist either.

Well, it’s still there and can still be used, so we can’t talk in a

past tense.

It’s regarded as the older server side font handling and referred to as

the Core X font subsystem.

When it’s used the X server handles the rendering, and loading of the font.

It loads and stores each character inside the X server and so the font

is accessible to anyone that is connected to it, it draws them upright.

However, it doesn’t support nor antialiasing nor subpixel rasterization

and you have to use a weird notation called XLFD, X Logical Font

Description to specify which font you want to use. Moreover, it’s only

recently that it started to support scalable font as it only supported

bitmap fonts before.

Utilities such as xfontsel and xlsfont help you choose the

configuration for the XLFD and the font locations need to be hardcoded

in an X11 configuration file by adding values to the FontPath directives

or by running the xset fp command.

So in that scenario the X server does all the heavy work.

But it is not very flexible and doesn’t render smooth fonts so things

slowly got decoupled and let the handling of fonts to be done by clients

instead and that’s where the RENDER extension we talked about was born.

As with everything graphic you need a layer that would be used to send

the glyphs and handle the graphical side.

Other than the Xlib and XCB that are used for the communication with X11

we have, as with any X application, libraries that deal with optimizing

the rendering for specific video hardware and output formats.

For instance the Cairo library is optimized for 2D graphics, SDL too,

OpenGL for 3D, etc.

Namely, the most used libraries to interact with the X RENDER extension

are Xft, the semi-obsolete generic replacement of the X Core font,

Cairo for the GNOME stack, Qt for the KDE stack.

That resolves sending the glyph to the X server, but we still got a lot of

things to do, we have to get the font, load it, rasterize it, clean it,

customize it, etc.

Xft, Cairo, and Qt, other than interacting with the X RENDER extension act as interfaces to the Freetype font rasteriser. They sit in the middle.

FreeType is the most popular font rasteriser library on Free Unixes, it’s small, efficient, highly customizable, portable, and under two free licenses, a BSD-like one and a GPL one. FreeType has the widest range of supported font formats in the world. Thus, it’s used in a lot of places like the Android operating system, the playstation, Apple uses it next to its AAT in iOS and macOS, and it’s used in the OpenJDK platform.

As we’ve discussed, rasterizing is the process of rendering text into bitmaps and using some techniques to make the text clearer on the screen. FreeType provides that easy to use and uniform interface to load and access the content of font files and get back a nice bitmap of the glyph requested. FreeType provides a way to tell it to activate auto-hinting, TrueType bytecode hinting, which is the embeded font hinting, antialias, sub-pixel rendering, etc. It does all we mentioned earlier if we ask it to.

So to recap so far we have that: A have a graphic handling layer sitting between the X RENDER extension and FreeType, which is the font rasteriser.

One thing that needs to be mentioned is that some of those libraries sitting in the middle apply some fancy changes to the glyph themselves before sending it rather than having FreeType doing it. For instance, Cairo can do sub-pixel rendering and filtering itself, Qt falls back to a FIR filter when FreeType doesn’t offer filtering, and Xft offers some intra-pixel filtering.

That’s cool, now we need something that will tell FreeType which font to load, to select and what kind of pretty changes it needs to apply to it. That’s a job for a font configuration engine that goes by the name of Fontconfig.

The job of Fontconfig is to provide an interface for font discovery and

configuration, such as if hinting is activated for a specific font or not.

One of its job is to always match a font whenever the case, if the

current font doesn’t support a character it should transparently fall

back to another font if possible.

And it supports utf-8 all the way so it always yields reasonable results.

Its font selection mechanism is very convenient and expressive, it let

users match fonts according to patterns and characteristics such as if

the font is slanted, bold, its size, etc.

We’ll discuss Fontconfig specifics in one of the next section.

At this point we’ve got rendering, rasterizing, and font selection and configuration, you would think that this would be enough but the font stack doesn’t end here. There’s yet another layer if you remember correctly and that is the font layout engine.

They are FriBidi, HarfBuzz, ICU, m17n, and SIL Graphite. Those engines are mainly used to support internationalization, as in multiple different languages with different shaping and layout rules. Let’s only discuss one of them, HarfBuzz.

It sits on top of FreeType as an OpenType Layout engine, opentype being

the de-facto font format that support complex text rendering on Free Unix.

It’s the library that actually understands the sophisticated features

inside the font. It keeps track in a sort of state machine of the glyphs

that need to be drawn, rearranged, reshaped, inserted, in different

situations and contexts.

It’s context sensitive.

Without a layout engine you wouldn’t be able to type correctly in certain

languages because they aren’t a one to one mapping between the character

you enter and the glyph that appear.

Simply said it takes complex unicode text and spurts out the right

glyph indices and right position where they should appear taking in

consideration the whole string.

Now finally the font stack is complete.

Atop of this stack there are even more abstraction layers such as Pango

which is like a roof supporting different sorts of font layout backends.

For instance Pango is used in GTK and it regroups Cairo or Xft plus

FontConfig for the font configuration and HarfBuzz as a layout engine.

But Pango doesn’t stop there, it’s multi-platform.

The font files, format and information

Finally, we got a bit of an understanding of this russian doll. Now we can take a bit of time to explore what’s inside some font files. Let’s first name some of the formats that are supported by FreeType:

- TrueType fonts (TTF) and TrueType collections (TTC)

- CFF fonts

- WOFF fonts

- OpenType fonts (OTF, both TrueType and CFF variants) and OpenType collections (OTC)

- Type 1 fonts (PFA and PFB)

- CID-keyed Type 1 fonts

- SFNT-based bitmap fonts, including color Emoji

- X11 PCF fonts

- Windows FNT fonts

- BDF fonts (including anti-aliased ones)

- PFR fonts

- Type 42 fonts (limited support)

N.B.: TrueType and OpenType are mostly identical even some fonts with a ttf extension are actually OpenType fonts. They use the same container format sfntf.

Let’s revisit our definition of what a font is.

A font is a collection of various character images that can be used to display or print text. The images in a single font share some common properties, including look, style, serifs, etc. Typographically speaking, one has to distinguish between a font family and its multiple font faces, which usually differ in style though come from the same template.

In some cases the whole font family can be represented by multiple files where each file represents a different face of the font. In some other cases all the faces of the font are included in the same file, which we call a font collection file. And thus a single font file might in fact just be a single font face of a font family.

Those files may contain character images named glyphs, character metrics,

information regarding the layout of the text and processing of specific

character encodings.

It’s important to note that a single character can have several distinct

images, as in different glyphs that can be used depending on the context.

There are also cases where multiple characters joined together can form

a single glyph.

This relationship between characters and glyphs is complex and that’s

what the layout engine we talked about handle.

Each glyph has an index, and the font file contains a table called the

character maps which is used to convert character codes for a given

encoding. There can be multiple charmaps per fonts.

Remember when we said that the layout engine job was to handle which

correct glyph index was to be returned in what situation.

Also associated with the glyphs there are various metrics to describe

how and where to place and render the text, and how much point should

the cursor advance forward after the text insertion.

Metrics are extremely important for the text flow.

And remember that all the metrics are expressed in points and not in

pixels, expept for bitmap font formats.

And that’s what’s contained in a font file.

How are they managed

Let’s return to the management part of the fonts, the part that Fontconfig

takes care of.

Fontconfig provides many utilities all starting with the prefix fc-.

For instance:

fc-list #lists all fonts available and cataloged for usage in X11 programs

fc-query #to query font files

fc-match #to try to match an available font or alias used to describe the fontFontconfig by default track down the fonts inside certain default

directories such as /usr/share/fonts and ~/.local/share/fonts. It’ll

traverse them recursively looking for all available fonts in them.

Fontconfig uses XML files in the /etc/fonts directory to generate its

own internal configs. By default, it parses /etc/fonts/fonts.conf which

sets some default options such as the default directories to read

font from we just mentioned. There are also the equivalent for local

user configuration which take precedence over the global ones.

The /etc/fonts also contains a conf.d subdirectory that has additional

configuration files covering different aspect of fontconfig. These files

start with a number indicating the order in which they are executed.

Now you might remember the time I mentioned that hinting was only great when it was done before antialiasing, well, that’s where you choose the order of things. Usually distributions offer some presets files and you symlink them inside that directory, as it’s very tedious to create your own. For example, to enable sub-pixel RGB rendering globally:

cd /etc/fonts/conf.d

ln -s ../conf.avail/10-sub-pixel-rgb.confIn those files you can also pinpoint how the fallback mechanism will

take place and change it.

I won’t cover all the different things that can be in those xml files

but again, there are links in the show notes discussing this in details

and you can also refer to the fonts-conf man page which is not bad at all.

To find out what settings, fallbacks, etc. Are in effect for a font you can use:

fc-match --verbose 'some font'Now how do we go about installing a font.

- Simple we download the font we want in a format supported by FreeType.

- We move the font to a directory managed by Fontconfig and make sure its readable.

- Update the Fontconfig cache by running

fc-cache.

That’s it!

Remember that for the X core fonts you have to do that at the X server level and it’s not as simple. You’d have to mark the directory as an X core font dir and then tell the X server to consider using them:

mkfontscale $dir

mkfontdir $dir

xset +fg $dir

xset fp rehash # Forces a new rescanOr instead of all that hassle you can rely on your package manager.

Don’t forget some commands

Let’s name some useful commands related to fonts.

xrdb— the xresources database, some fonts can be set there for some applicationsxfontsel— point and click selection of X11 font namesshowfont— font dumper for X font serverxlsfonts— List all the fonts on your systemfslsfonts— List fonts served by X font servermkfontdir— create an index of X font files in a directoryfsinfo— X font server information utilityfstobdf— generate BDF font from X font serverxfd— display all the characters in an X fontchkfontpath— simple interface for adding, removing, and listing directories in the X font server’s pathTrueTypeViewer– a free, powerful OpenType viewing tool with a TrueType instructions debugger (not using FreeType)freetype2-demos— A series of tools to debug freetype fonts

There are some gnome configuration tools such as:

gnome-font-properties

gnome-font-viewer

gtkfontselNotably there are all the Fontconfig tools we mentioned before fc-.

There are utilities to convert from one font type to another.

dxfc

bdftopcf

bdftosnf

mftobdf

fstobdfUtilities to edit bdf, bitmap fonts:

bdfresize - a bdf font resizer

xmbdfed - a bdf font editorTo view some otf or ttf fonts you can even use a web interface, some

websites offer that.

You can use image magick to display all the characters inside a font by

issuing the dipslay command:

display fontname.ttf #part of imagemagickSome utilities like Fontmanager and fontmatrix lets you organize

groups of fonts to be installed or uninstalled, and you can preview them

and see their features, whether installed or not.

The last utilities to mention are the utilities that can manipulate the settings of the xserver itself, the ones stored in the XSETTINGS specification.

Tips

Here are some tips.

N.B.: There’s something called Infinality that regroups a set of patches for FreeType with a bunch of preset for Fontconfig. It is said to show higher quality rendering but as we’ve said earlier that definition is somewhat subjective.

N.B.: The JRE, Java Runtime Environment fonts are harder to configure you have to set some environment variable so that they respect the antialias and hinting you want. So next time don’t rage when you see ugly font inside a java application and go set those up.

N.B.: Fonts are not limited to text, a lot of fonts are emogi or

pictographic fonts. They are widely used around the internet as icons

sets and is also used a lot in the ricing community to decorate bars.

If you’re falling short on Unicode fonts there’s a link in the show

notes that regroup many great libre open source fonts in all languages.

It’s called unifont.org, see http://unifont.org/fontguide/

N.B.: There are fonts that are metric-compatible together.

It means that their metrics match, and as you remember the metrics are

everything related to the size of the glyphs. Those fonts when they have

the same face can be used interchangeably as replaceable fonts without

changing too much the aspect of the text.

Remember that in your next web project when you want to provide fallback.

Making your own font

Let’s discuss making your own font and typography. To make your own font you don’t truly have to be an expert typograph but having some knowledge could help.

The world of typography is freaking huge and that’s not a surprise,

writing has existed for a long time and it’s obvious that there would

be a domain of expertise being built around it.

If someone claims they “know” typography it’s probably just that they

have a vague idea of some concepts. You must be a graphic designer or

someone who has a background in this field to be versed in the art of

typography. I’m not one of those.

I had thought about including a section in this podcast about typography,

but I was too overwhelmed.

Nevertheless, I’ve linked resources in the show notes that could get

you started if you wish to.

Now back on topic, if you want to create or edit a font on Unix there’s

a software called fontforge.

It’s a very advanced software with all the features you’ll ever need.

On their official website they have a book called “Design With Fontforge”

which seems like a wonderful book. It goes through all the steps needed

to understand what fonts are, typography, the vocabulary, the anatomy

of glyphs, and how to design a font.

Yep, glyphs even have their own anatomy.

Conclusion

As I’ve said in the beginning of this podcast, fonts are a deep topic, and so I encourage you to read from the links I’ve added in the show notes. What enraged me when starting this research was that there was no clear document discussing the font stack of current Unix-like operating systems. I truly hope this podcast enlightened you as much as researching for it did for me and that I haven’t messed up any info.

Yep. Those are the fonts!

References:

- TTY:

- https://github.com/talamus/rw-psf

- http://askubuntu.com/questions/173220/how-do-i-change-the-font-or-the-font-size-in-the-tty-console

- http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/161890/how-can-i-make-a-psf-font-for-the-console-from-a-otf-one

- https://www.freebsd.org/doc/en/articles/fonts/article.html

- https://wiki.freebsd.org/Newcons

- http://www.openbsd.org/faq/faq7.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linux_console

- https://nixers.net/showthread.php?tid=552

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glyph_Bitmap_Distribution_Format

- http://sofia.nmsu.edu/~mleisher/Software/gbdfed/

- Locale & UTF-8:

- http://www.in-ulm.de/~mascheck/X11/input8bit.html

- http://michal.kosmulski.org/computing/articles/linux-unicode.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open-source_Unicode_typefaces

- http://stackoverflow.com/questions/20226851/how-do-locales-work-in-linux-posix-and-what-transformations-are-applied

- http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/87745/what-does-lc-all-c-do#87748

- https://docs.oracle.com/cd/E23824_01/html/E26033/glmbx.html

- http://www.unix.com/unix-for-dummies-questions-and-answers/117-how-change-locale.html

- http://www.in-ulm.de/~mascheck/locale/

- Font files:

- https://www.freetype.org/freetype2/docs/glyphs/glyphs-1.html

- Rendering (FreeType):

- http://userguide.icu-project.org/layoutengine#TOC-Overview

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_Advanced_Typography

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Font_rasterization

- https://freddie.witherden.org/pages/font-rasterisation

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FreeType

- https://www.freetype.org/freetype2/docs/glyphs/glyphs-5.html

- https://bbs.archlinux.org/viewtopic.php?id=33955

- https://keithp.com/~keithp/talks/xtc2001/paper/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subpixel_rendering How subpixel rendering works: * https://www.grc.com/ctwhat.htm

- http://www.osnews.com/story/18166/Interview-with-David-Turner-of-Freetype/

- http://behdad.org/text/

- MacOS:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fonts_on_Macintosh

- Stack:

- https://weirdfellow.wordpress.com/2010/07/25/insanity/

- https://weirdfellow.wordpress.com/tag/freetype/

- http://www.pango.org/

- https://kb.iu.edu/d/aytm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:GTK%2B_software_architecture.svg

- http://roxlu.com/2014/046/rendering-text-with-pango--cairo-and-freetype

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pango

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HarfBuzz

- https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/HarfBuzz/

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/X_Logical_Font_Description

- http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/7461/how-does-linux-manage-fonts#7483

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X_Font_Server

- https://specifications.freedesktop.org/xsettings-spec/xsettings-spec-0.5.html

- https://mrandri19.github.io/2019/07/24/modern-text-rendering-linux-overview.html

- Generic Management (Fontconfig):

- http://tldp.yolinux.com/HOWTO/Font-HOWTO.html

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Fonts

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/font_configuration

- https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-US/Red_Hat_Enterprise_Linux/7/html/Desktop_Migration_and_Administration_Guide/configure-fonts.html

- https://wiki.gentoo.org/wiki/Fontconfig

- https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Guide_to_X11/Fonts

- http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/fonts/X-Window-System-fonts.html

- https://www.freebsd.org/doc/handbook/x-fonts.html

- https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/fontconfig/

- http://www.yolinux.com/TUTORIALS/LinuxListOfFonts.html

- http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/5715/how-to-view-a-ttf-font-file

- https://bbs.archlinux.org/viewtopic.php?pid=923075

- Tips:

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Java_Runtime_Environment_fonts

-

https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Metric-compatible_fonts

- Creating fonts:

- https://fontforge.github.io/en-US/

- http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/everything-need-create-fonts-free/

- https://superdevresources.com/create-your-own-font/

- Typography:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_typefaces

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sans-serif

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serif

- http://www.happytypings.com/alphabet/

- https://www.fonts.com/content/learning/fontology

- http://www.noupe.com/essentials/icons-fonts/a-crash-course-in-typography-the-basics-of-type.html

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Metric-compatible_fonts

Attributions

Unknown author / Public domain

If you want to have a more in depth discussion I'm always available by email or irc.

We can discuss and argue about what you like and dislike, about new ideas to consider, opinions, etc..

If you don't feel like "having a discussion" or are intimidated by emails

then you can simply say something small in the comment sections below

and/or share it with your friends.