(Transcript of the podcast)

(Transcript of the podcast)

Continuation of the podcast on X11, xcb, wayland, etc.

We’ve had a previous episode discussing xcb, x11, wayland, all about

display servers.

I’ve said in the beginning of the episode that it would not be about

window managers.

Well, today folks we’re going to do just that.

This one is going to be about window managers and desktop environments.

Thinking about Human-computer interaction

What does HCI mean

There’s a field of study called HCI, which stands for human computer

interaction. Its domain of interest is how users interface with a machine,

especially in findings new and more efficient ways to do so.

This research field is as the intersection between behavioral science

and computer science, it’s a sort of dialogue with a machine.

And like any dialogue we want our thoughts to reach out the other party.

The ACM, Association for Computing Machinery, defines human-computer

interaction as “a discipline concerned with the design, evaluation and

implementation of interactive computing systems for human use and with

the study of major phenomena surrounding them”.

It’s a field of study that started appearing in the mid 70s.

In the world of HCI there are many designs, principles, methodologies and ways to research how efficient an interface is. But it always strives with ingenuity, always trying to take the best out of both sides, the computer, and the human. The factors change, it goes both ways, the computers evolve and the HCI theories evolve accordingly.

The desktop metaphor & WIMP

Why are we talking about HCI to begin with? Because it’s the core of the topic, it’s the bone supporting our story. Everything stems from it. People have always taken a look at the computers and technologies available for the time and wondered what type of interactions would be possible.

We first used the computers in batch mode using punched-cards as input

then we switched to a more interactive approach through text display using

command line interfaces and now through raster graphic based computers we

use graphic interfaces, and we’re still in the transition to a new phase.

The advent of the graphical user interfaces or Gui, “gooey”, gave rase to

new paradigms.

Rather than having only text, users are now presented with images.

The user interacts in this environment using a keyboard and a pointing

device, typically a mouse.

The user has to manipulate the graphical elements on the screen.

The field of HCI denoted a new type of paradigm called the WIMP graphical user interface: Windows, Icon, Menu, Pointer. HCI emphasis on making the user interface as seemless as possible with the real world so that non-technical people can still understand what is going on without surprises. They do that by using metaphors of the real world.

And that’s where the desktop metaphor comes from, it contains windows, which are like sheets of paper, folders, or trashcan, etc. The navigation is frictionless and more efficient compared to text user interfaces, but not necessarily as powerful. The elements of the WIMP came to be through iterations of what made the most sense for users. It doesn’t require a steep learning curve. But how did this came to be and what’s the relation?

That’s a quick, vague, and nebulous intro to what we’re going to discuss in this episode. It has set the ground for more discussion about the core of our topic and emphasis the interaction part of it.

What’s a window manager

What’s a window?

A window is like the window of a building that allows to see outside.

In a graphical user interface it describes a canvas, usually a squared,

but could be any shape, section of the sreen, which surface is painted

with the application.

It’s a window to give you a view of only that application.

An area of visual display.

The applications draw on that specific region all of its component, and that window stays cohesive together as one block, it’s self-contained. The size and position can normally be adjusted, and the windows may or may not overlap, in all cases the content of the window is independent of this.

This window metaphor has worked great and is adopted everywhere alongside the desktop metaphor. On Unix specifically, the style of the window is normally dictated by the widget library that is in use for that program. The widget library offers widgets such as text inputs, menus, scrollbars, dropdown, etc. We’re not going to discuss those here but might do a podcast about them later on.

Windows can also have a decoration drawn around each of them, but that is dictated by the window manager and not the window itself.

But what’s a window manager?

What’s a window manager

The window manager doesn’t handle what’s inside the windows but instead handles their management, just like the name implies. It dictates how the windows are controlled and where and how they are displayed.

The windows are like the papers and the window manager like the

combination of the desk and your hands, that you can respectively use

to lay and manipulate the papers.

Or more precisely the window manager would be your eyes plus hands

plus desk.

What you currently see with your eyes is called the viewport and it has

a limit, while the desk may not or may be bigger than your viewport.

The viewport is the destination display space, it’s a view onto a large virtual world. A viewport is usually the size of the screen but that’s not set in stone, each window manager can take a different approach to this. Viewports might also be referred to as virtual desktops in certain window managers. Some refer to window managers that have many viewports, as virtual window managers.

Generically, window managers have two parts, the presentation, which displays windows and lay them around the screen, and the operations which is how the user enters commands to manipulate those windows. This is a vague overview of the basic and that gives rise to many possibilities and implementations.

Let’s dive into the history of HCI and then come back to unpack those possibilities that are currently available on Unix operating systems.

History of HCI

As we’ve said HCI emerged in the mid 70s and that’s no coincidence as we’ll see.

History and concepts that were added one upon the other

Let’s go through an overview of window interfaces and concepts that influenced current graphical user interfaces.

If we could traceback history and put the praise on a single individual for starting the spark of it all that would be Douglas Engelbart in the 60s for his work at the Stanford research institute. He is considered one of the founders of HCI and more or less has invented the concept of window, along with the concept of a pointing device, the mouse. Before that we certainly had terminal multiplexers and/or curses interfaces but those weren’t graphical in the sense we mean. However, we can’t deny their influences on the later designs.

Most of the genuinely new ideas originated from one place, Xerox PARC,

Palo Alto Research Center.

Their mission was to “investigate the possibilities of new computer

systems to be used in offices, assuming that in the future computer

power would be abundant and inexpensive.”

The Smalltalk environment, based on the smalltalk OOP language, developed

at PARC in the 1970s, introduced the first floating windows, windows

that could overlap and move easily.

This lead into further improvement of the concept of GUI, thinking about

new techniques and possibilities to interact with these windows.

This was the start of window management.

Smalltalk contained a lot of innovative ideas like cut-and-paste, pop-up

menus, a browser, a clock.

Then came a more commercial approach to this system, in 1975, the Xerox

Star was released.

It was the first real consistend graphical interface that used the notion

of an office where the user operates on tasks, the office metaphor or

the desktop metaphor as we call it today.

It consists of windows, menus, buttons, radio buttons, icons, and uses

a keyboard and a pointing device for interaction.

It was the creation of the WIMP paradigm.

From that point on that influence Xerox had spread like the flea,

everyone implemented and re-implemented the WIMP design.

Let’s go over some of them following a chronological order.

Rob Pike and Bart Locanthi at Bell Labs in 1982 design the Blit, a

programmable bitmap graphics terminal.

It was similar to a plain textual terminal but could also load software

that would use the terminal graphic capabilities.

On that Blit people would usually load a window system, mpx, later

mux, which replaced the terminal interface by a mouse-driven graphical

multiplexer.

It could run terminal emulators, editors, clocks, etc.

The mpx and mux wm had a minimalist design and it was what later inspired

the X window system running on most Unix systems today.

It was the first system to separate the window manager from the drawing

mechanism.

This was all around 1982.

Later on in 1983, Apple released the Apple Lisa, which user interface

was highly influenced by the Xerox Star but didn’t take off commercially.

After that, in 1984 the Macintosh was released. It was peculiar in a

sense that the screen, the keyboard and the mouse where attached to the

box containing the hardware.

It introduced an intuitive and clean interface, at least cleaner than

other competitors.

In 1985 Windows 1.0 was released. It wasn’t particularly innovative but

it brought the graphical user interface to the masses.

In the late 80s, early 90s NeXTSTEP got released.

NeXTSTEP was UNIX based, using the Mach kernel plus a bit of BSD

sources. It was ahead of its time when it came to graphical UI.

The first web browser was created on NeXTSTEP, games such as Doom,

Wolfenstein 3D, and Quake were also developed on it.

NeXTSTEP was the pioneer in the toolkits or graphical widgets we have

today.

And we’ll stop the history there, pardon me if I didn’t mention so

many other influential window managers but I have to cut it short.

You can find a graph showing how window managers influenced each other

in the show notes for that.

So, summary of things to remember:

- In the 60s we have Douglas Engelbart

- Smalltalk in the 70s

- Xerox Star in 1975

- The Blit in 1982

- Apple Lisa in 1983

- Macintosh in 1984

- Windows 1.0 in 1985

- And, late 80s, start 90s we have NeXTSTEP

Most of the window management techniques available today originate from those times. We should be grateful of their influences. Let’s focus on the specific Unix bloodline.

The WM bloodline of Unix

(Disclaimer, I’m not going to talk about MacOS nor NeXTSTEP anymore.)

So what’s particular about Unix?

Some of the bloodline

While the User interface of MacOS and Windows have started their iterative

process in the mid 80s, in the rest of the Unix world user interfaces

were not set in stone.

At the same time around 1984 the X window system was created. It followed

the same architecture of Blit, a minimalist server architecture.

Consequently, all window managers for Unix-like operating systems are

implemented as a server process outside the memory space of the client.

If you want more info on the specific architecture you can refer to the

podcast on X11, xcb, wayland, etc.

As with the Unix fashion, nothing is set in stone, and everything

is flexible. There are hundreds if not thousands of different window

managers.

In more details, the window manager keeps running and whenever there’s an

attempt to show a window the window manager will receive a request. The

window manager then chooses what to do with it, map the window and where.

The window manager can choose to draw, or to use the specific term “map”,

the window directly on the screen, the root window, or to reparent it

over another window it has draw, let’s say the borders or decoration,

title bar, the frame.

The window manager works in a sort of loop where it receives notifications

of events happening on the windows or when certain keys are pressed,

it’s event driven programming.

It receives all sort of events, from mapping request, unmap requests,

resize, iconify, etc.

Keep in mind that the window manager has full control on what it does

to the windows.

There are standards regarding what to do when receiving certain events

and a window manager can choose to respect them or not.

Those are the freedesktop standards, and they also include inter-client

communication convention, ICCCM, and extended window manager hints EWMH.

They allow a window managers to work fine with other applications like

bars or panel for example.

For instance, the ewmh uses a feature of the X server which allows

storing hints, properties, key/value pairs, meta information on windows.

You can use the xprop tool to examine them.

Those are there to provide a better experience and interaction with

other widgets that may be part of the desktop but are not enforced.

For example the root window may contain a _NET_CLIENT_LIST property

which has a list of all the currently windows opened or a window may

have the _NET_WM_NAME property which has the name of the program that

is running inside the concerned window.

You can give the specs a look, it’s in the show notes.

What kind of features do window managers have

Even though nothing is enforced for a window manager to work on Unix-like systems, there are still a bunch of characteristics that stand out as common between many of them. Nevertheless, this is still just an overview of what a WM can do and is supposed to do. Don’t take anything I’ll say as a given. Window managers can add so much more to their arsenals or arguably much less. We said we’ll come back to it, so we’re coming back.

Window managers have only two basic roles or goals, displaying/laying on the screen/presenting windows, and controling/manipulating windows. Or on a much broader level, their role is to be the intermediary between the displaying and controling. That’s all there is to it, the basics of basics, anything else added is an extra feature given by the window manager.

Now this interaction should unfold somewhere, and that somewhere is the

viewport, as we’ve mentioned ealier.

It sort of stands between the two as both control and display at the

same time.

As a reminder, the viewport is used as a virtual workspace and makes

switching between different tasks easier because the user doesn’t have

to remember the arrangement or re-arrange the windows for every task.

There’s a concept here that every window manager should try to avoid

and it is the “WindoItIs”, the cluttering of the screen. This state of

quick disorientation and lost of relationship between windows.

The constant user struggle to arrange and re-arrange windows,

house-keeping them.

Every window manager should try to avoid this.

layout strategies

There are many layout strategies that a window manager can take but some are more predominant than others.

A layout strategy is the way the window manager handles placing the windows on the screen. We will go over the most important ones like stacking, tiling, and dynamic.

Tiling WM

The tiling approach organizes windows on the screen so that they are mutually non-overlapping. No other window covers the space where another window is drawn. It is similar to a ceramic tiles on the floor. It’s like a really tidy desk where all the papers are always laid open.

With tiling, the window manager takes over from you the management of

window placement and size. You don’t have to think about them anymore,

it’s all taken care off.

Tiling achieves this through multiple types of algorithms each one laying

the windows in tiles but differently.

Some tiling algorithms allow resizing windows and change their places,

some don’t.

The most common approach is that when one window is opened, it fills the

whole screen, and when a second window is opened the screen is divided

horizontally or vertically to make space for the new window, and so on.

But tiling is not limited to filing the whole screen, some spaces could

be dedicated for certain purpose.

One issue with the tiling layout strategy is that popups result in unexpected resize and replacement of all the other windows on the screen. Another issue is that with small screen, windows will fastly shrink. However, it takes the burden from the user to not think about window placement and size.

Stacking wm

The stacking approach is closer to the traditional desktop metaphor, window act like pieces of paper on a desk that can be stacked on top of each other.

The window manager, in most cases, doesn’t enforce the size and placement of windows. And thus the user has to do that him/her/self. The user can move windows and resize them, bringing them in the front of the stack or under it, obscuring some regions of one another.

The advantages with tiling is that popups don’t hinder the user, and that multiple big windows can be shown on a relatively small screen simultaneously. The disadvantages are that the user has to always take care and think about placing windows.

Extra

The layout strategies are not limited to stacking and tiling only, a window manager can combine both of those and let the user switch between them at will. That is referred to as a dynamic window manager.

Control Strategies

What sort of control strategies can be included in a window manager,

what techniques can be used to manipulate windows.

The basics of manipulation lay into four operations: to add/map a window,

to delete/unmap a window, to reposition/move a window, and to resize

a window.

In tiling WMs the move and resize part might be totally taken care of by the window manager. For others the manipulation could be implemented using keyboard shortcuts or a pointing device.

You can actually use anything that is an input device to your machine.

However, the most commons ones are the mouse and keyboard. Mouse

oriented window manager being a bit more friendly than keyboard oriented

ones. Simply because remembering keyboard shortcuts is another burden

on the user. But on the long term may become faster than to employ the

mouse for every operation.

Most tiling window managers employ the keyboard driven approach if they

ever allow resizing and moving windows but it’s not limited to them,

a stacking window manager may well provide keyboard accelarators or

shortcuts.

The goal of window control and management is to avoid the concept we

mentioned earlier, remember the “WindowItIs” syndrome, the one where

the user gets disoriented and looses the relation between windows.

Well, the control part of a window manager is the housekeeping, the

management part.

And so window managers offer a bunch of other features related to control

that are not in the basic four operations.

For example a window manager may offer the possibility to maximize and

minimize a window, as if it was stored away in a drawing for a while.

A tagging system may also be implemented to group windows together and

apply “bluk” operations on them.

The virtual desktops or viewports are also a way to manage and control

windows, it’s similar to tagging as it groups them by separate view ports.

The window manager can go a bit further by giving windows states and

changing their decoration accordingly to give a visual clue about which

states the window is currently in.

All of those to make management and control easier on the brain.

Last but not least, let’s take in consideration that the window manager is just a middle man between the X server and the user. And so, some projects even take away the control part of the wm and replace it by some third party tools. For instance there are the wmctrl tools, the sxhkd that is popular with bspwm users, and the wmutils by dcat and z3bra at nixers.

You should always keep your mind open for new concepts when thinking of window managers.

Whatever goes goes

So what else differs between the window managers, why would you prefer one over another? There’s a lot to try, different approaches to this problem. Let’s name some differences:

- The programming language its written with

- The memory footprint and cpu consumption

- The type of layout strategy

- The type of control strategy if it even includes control within it

- How it looks, the visual aspect

- The customazibility of the appearance

- The customazibility of the control

- The way the configuration file is written, if it has one

- If it has the concept of viewports or virtual desktops and how it implements it

- If it offers extra features like menus, bars, panels, docks, program launcher, etc.

- The degree of integration with a desktop environment

- If it’s a composite window manager: Compositing wm that is if the window manager composites the window buffer into an image representing the screen and writes it directly into the display memory. So it can apply 2D and 3D animated effects, all sorts of visual effects.

You can see the list and comparaison of wms in a link in the ArchWiki link in the show notes.

Wayland anyone?

A small mention on wayland compositors… Like the name says, wayland compositors are composite.

The big different with window manager is that compositors contain within themselves the windowing server, they are windowing systems and window managers at the same time. That’s all I’m going to say, refer to the earlier podcast for more info.

Many Choices + flexibility

Let’s emphasis this again because it’s quite hard for some beginners to grasps this. And let me quote from the ArchWiki:

Unlike the classic Mac OS, macOS (Apple Macintosh) and Microsoft Windows platforms which have historically provided a vendor-controlled, fixed set of ways to control how windows and panes display on a screen, and how the user may interact with them, window management for the X Window System was deliberately kept separate from the software providing the graphical display. The user can choose between various third-party window managers, which differ from one another in several ways.

And thus this leaves the users to run wild with their imagination

taking whatever they want from this confluence of ideas, cherry-picking,

re-inventing, re-using, whatever suits them.

It is like a fashion show, everyone peacocks their most fabulous desktop.

Confluence of ideas and influence taken from one another.

That gave rise to a movement called ricing which we may talk about in another podcast. Many of the people on nixers are into this movement and so if you want more info about it, you can simply ask them.

Desktop environments

What about DE

Remember we talked about extra window managers features like bars,

panels, and docks.

Those extra bits can be bundled in the wm or outside, offered

as a third party by the environment.

Yep, because the window manager doesn’t live alone, it’s part of a series

of programs that make your machine usable in the graphical world.

All those pieces join together to create what we call a desktop

environment.

The linking and communication is done using what we talked about earlier,

ICCCM and EWMH but it doesn’t have to use them, it’s not forced.

So truly, what’s a desktop environment? Let’s read a quote that sums this up:

A desktop environment bundles together a variety of components to provide common graphical user interface elements such as icons, toolbars, wallpapers, and desktop widgets. Additionally, most desktop environments include a set of integrated applications and utilities. Most importantly, desktop environments provide their own window manager, which can however usually be replaced with another compatible one.

The name stems from the fact that most desktop environments are implementations of the desktop metaphor even though a lot go beyond that. It would be more precise to refer to it as the “graphical shell” but the name desktop environment sticked.

Bundles

So what does it mean when you hear someone utter that they “installed a desktop environment”. It means that they’ve installed a bundle pack that came with a bunch of complementary goodies. Usually that bundle is made for convenience and or for novice users that don’t want to bother installing everything from scratch.

Those desktop environments also rotate around a core library and most of their applications depends on it to work well together and to keep a cohesive visual and control experience. Here are some of the most popular in 2016:

- Plasma - KDE Desktop

- Gnome

- Unity

- Cinnamon

- MATE desktop

- LXQt

- Xfce

- Budgie

- Pantheon

As with the WM, the choice is yours, checkout the features, then bundle of programs that come with the desktop environment, the feel of it, the memory footprint, the features, etc.

A last word on this topic. Some distros only differ by the DE they have installed by default and the packages they have installed inside of it. And thus changing between those distros is just a matter of convenience to not install the desktop environment yourself.

The choice is yours

And, as with everything on Unix, the user is free to choose and configure

whatever they like in their graphical environment.

You’re free to choose the window manager you want with all the softwares

you want to create your own desktop environment.

You can “rice” your desktop environment to your specific needs.

Customizing your tailor made environment.

This sounds great, right? So what kind of things can you include in your desktop shell other than the window manager?

- Taskbar, toolbars, dock, panels, bars

- Popups/notifications

- Compositor

- Icons are also, mostly separate

- Titles and borders

- Menus and program launchers

- Clipboard manager

- Virtual Workspaces - viewport

- Font colour

- virtual workspace.

- Program Launcher (wm acts like a graphical shell?)

- Third party compositing (add the composition feature)

- Wallpaper setter and desktop icons

- Screen locker

- Display manager aka login screen

- Sound volume manager

- Power Management Signaling and tools

- File manager and mounting tool

- Terminal Emulators

If you find that this sounds like a lot then you’re not wrong, it’s a lot because the desktop environment contains everything, any software that when working together creates your working environment. It can include any software that is needed for you.

Further thinking

Let’s take a moment and think further.

What we have today in terms of human computer interaction emerged from

the 80s and hasn’t evolved much.

It is still very limited but the desktop metaphor and the concept of

window has stood strong throughout all those years.

But that’s not a reason to stop thinking deeper and incorporate new

ideas together.

Projects like the Metisse at the university of Paris Paris-Saclay

implements new way to think about window management and interaction. I

truly urge you to take a look at it in the show notes.

Unix has its place in this innovation because of the way the window manager works with the X server, it’s flexible and open.

Another point we need to consider is how the devolopment of user interface

has evolved, it has always been a two-way street. The hardware becomes

more powerful, and we create an interface that works on this hardware

and force everyone to use it.

But today we need to think the other way around. We ask the user what

they need, find what they need, without worrying about hardware resources,

and we build an interface that is custom-made for their use.

This method of user-centered design, or well-tailored design, is the

future of window management and of graphical interaction as a whole.

Conclusion

That’s it! There’s a lot of window managers for Unix so go and try them out, make up your own mind about what you like and find that suits your workflow. And if you’ve always sticked with a desktop environment then it’s the perfect time to try to build your own custom environment.

Bear in mind that this podcast is just a shallow overview, for more info check the show notes, they’re full of awesome stuff.

Music

Jazz in paris

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human–computer_interaction

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WIMP_(computing)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graphical_user_interface

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Engelbart

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smalltalk

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Project

- https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Tiling%20window%20manager

- https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7b93/785d1d84b06d36badb59a0c6b779d76743c5.pdf

- http://www.chilton-computing.org.uk/inf/literature/books/wm/p004.htm

- http://toastytech.com/guis/star.html

- http://mnemonikk.org/talks/tiling-wm.en.html#sec-3

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blit_(computer_terminal)#Window_systems

- http://www.osnews.com/story/26315/Blit_a_multitasking_windowed_UNIX_GUI_from_1982

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DESQview

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_Lisa

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Windows_1.0

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extended_Window_Manager_Hints

- http://www.gilesorr.com/blog/wm-bloodlines.html

- http://www.gilesorr.com/images/blog/2015-12-02.wm.dot.svg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Windowing_system

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X_window_manager

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiling_window_manager

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_X_window_managers

- https://specifications.freedesktop.org/wm-spec/wm-spec-latest.html

- https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Specifications/wm-spec/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X_Window_System

- http://www.xwinman.org/

- http://www.gilesorr.com/wm/table.html

- https://sourceforge.net/projects/xynth/

- http://insitu.lri.fr/metisse/

- https://wayland.freedesktop.org/docs/html/ch02.html

- https://www.linux.com/news/best-linux-desktop-environments-2016

- http://www.howtogeek.com/163154/linux-users-have-a-choice-8-linux-desktop-environments/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desktop_environment

- https://seasonofcode.com/posts/how-x-window-managers-work-and-how-to-write-one-part-i.html

- https://www.uninformativ.de/blog/postings/2016-01-05/0/POSTING-en.html

Attribution

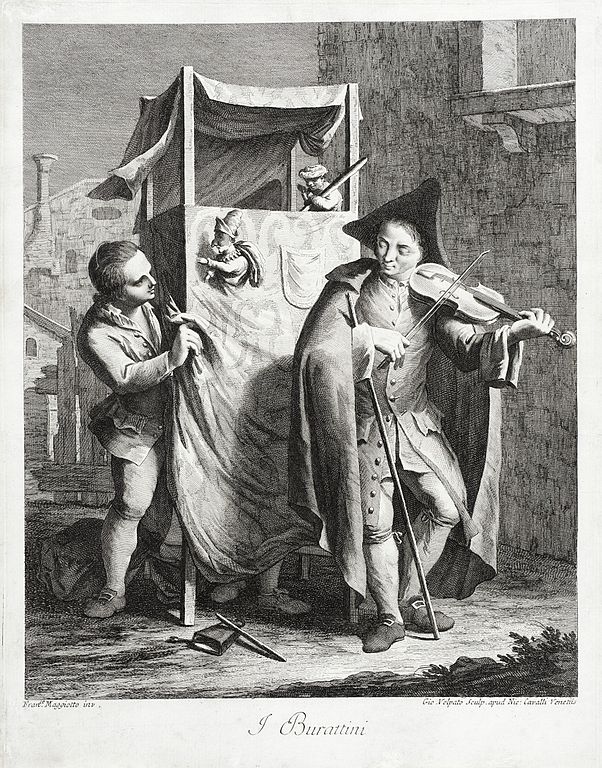

Los Angeles County Museum of Art / Public domain

If you want to have a more in depth discussion I'm always available by email or irc.

We can discuss and argue about what you like and dislike, about new ideas to consider, opinions, etc..

If you don't feel like "having a discussion" or are intimidated by emails

then you can simply say something small in the comment sections below

and/or share it with your friends.