https://nixers.net/showthread.php?tid=2164

Table of content

- Intro

- Ideas and concepts

- The overall generic architecture

- Lowest level - Hardware & limitation

- Mid level - Partitions and volumes organisation

- High Level

- A big overview of FS

- POSIX I/O

- MANAGEMENT, COMMANDS, & FORENSIC

- Conclusion

- References

Intro

Libraries and banks, amongst other institutions, used to have a filing system, some still have them. They had drawers, holders, and many tools to store the paperwork and organise it so that they could easily retrieve, through some documented process, at a later stage whatever they needed. That’s where the name filesystem in the computer world emerges from and this is one of the subject of this episode.

We’re going to discuss data storage on Unix with some discussion about filesystem and an emphasis on storage device.

Ideas and concepts

What’s data storage and what’s a file system?

Data storage is whatever mean that is used to store information on a medium that can contain that body of data and that offers a way to search for that information back.

The data storage medium we’ll focus on will be the long term physical storage devices, like hard disks, and not the virtual ones that only exist in memory or networked ones.

A file system is a way to give meaning to the placement of this

information instead of having it as a big blobs of 1s and 0s. A file

system helps by offering an interface to isolate, group, classify,

delimit, to know where the information starts and ends, give pieces of

information an identifier, a name, give the information different sort

of attributes like access rights and metadata, etc.

There are many kinds of file systems that can be used on

different types of storage devices, each one with different specificities

and ways of handling information.

So, we’ve delt with definitions, now let’s talk about the big architecture of all the components that are involved.

The overall generic architecture

To better understand the architecture of the data storage you have to

think about it as a sort of two-way street which has two roles, to read

or to write. Along the way the data travels that street and stops at

those components that are in the middle parts of the architecture.

Those components sometime keep a log of whatever passed through them,

they cache it so that they can cast away the request, pushing it back

to where it came from.

You can also think about it like every one of those nodes have both a

read and write methods and apply those methods to one another, though

it is not always as simple as that but it gives a picture of the flow.

Let’s go through the layers quickly so that we can grasp the overall

architecture.

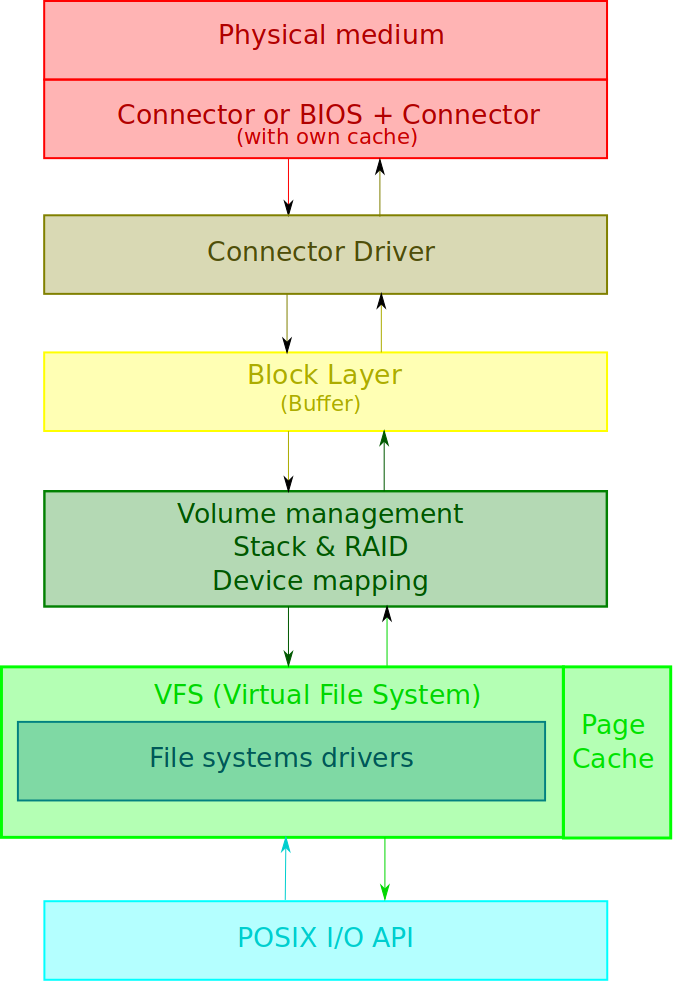

At the lowest of layers we have the physical device itself, be it an

HDD or SSD or DVD or SD or Flash, etc.

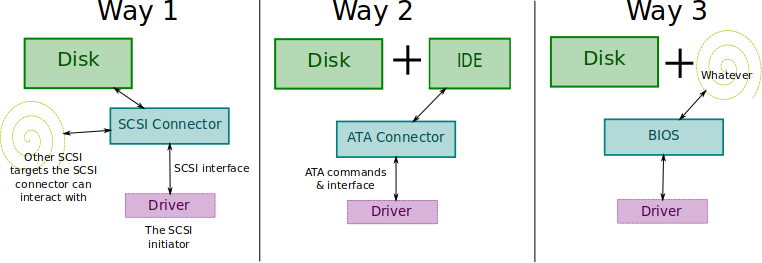

Those devices have a connector that speaks a certain transfer protocol,

which is usually a SCSI or ATA cable.

Above this we have the drivers that maps and interacts with those devices

via the connectors, not only to transfer data but also to configure and

read metadata from them.

On some systems, the driver interacts with the BIOS (basic input/output

system) instead of interacting with the connector directly. However,

on most Unix this is not the case, the driver speaks directly with

the connector.

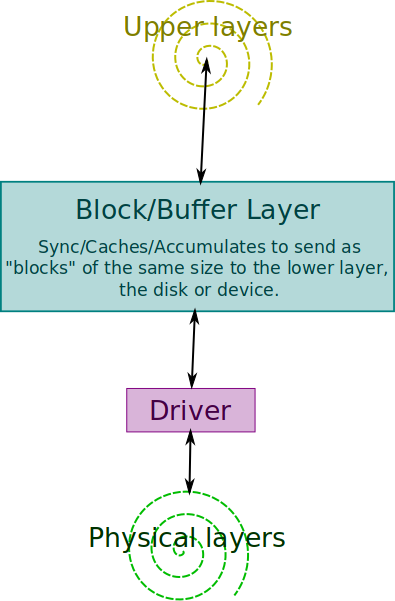

Above the drivers we have an optional block layer that buffers, schedules,

and queues requests that will be sent to the device. It also uses the

block as a unit independently of what the real unit of the device is. For

example, on a hard disk the sector size is usually 512 bytes while a

block could be 4096 bytes (this is related to the filesystem).

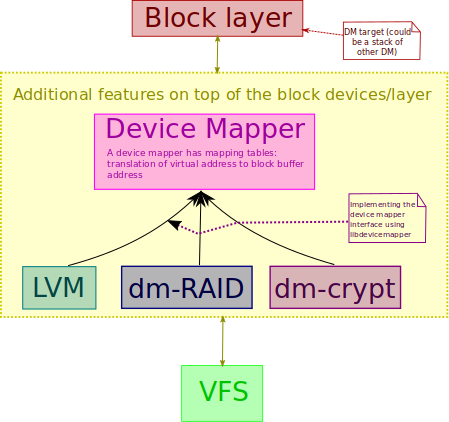

The next layer on top is optional and is composed of hardware abstraction

such as hardware encryption, disk spanning via LVM - logical volume

management or the MD driver on Linux, RAID for redundancy, etc.

Above this we have other abstraction layers that consist of the VFS,

the virtual file system, and the page cache that could possibly be paged

out to the physical device or used to cache some of the disk I/O.

The virtual file system is an abstraction layer that interfaces between

the user and the file system in use, its role is to give the same

interface whatever the file system in use. So the filesystem is sort of

within this layer too.

More precisely “The VFS provides the abstraction layer, separating the

POSIX API from the details of how a particular file system implements

that behavior.”

As you can see, those are blocks fitting into one another. Keep them in mind all along as we’re going to dive into every one of them one by one.

Lowest level - Hardware & limitation

The medium

Let’s talk about the hardware.

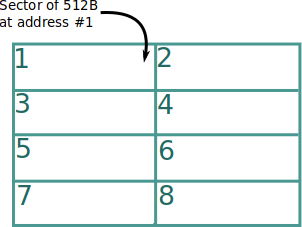

The lowest/minimal unit of storage on a medium is the sector. A sector

is a block/cell of bytes of a certain size. Some devices have physical

hardware sectors like hdd and ssd but others have it abstracted by

the software and have no physical delimiters. This makes the storage

medium a grid of cells that can be used to store data. Those sectors

are addressable, that means they can be pointed and found by reading

and writing at their specific offset, this makes searching and writing

information more efficient.

A lot of the logic, abstractions, and file placement optimization done

at higher levels (optimizing seek time for example) are and were made

with the assumption that we are interacting with a hard disk. So it’s

important to know the physical layout of a disk.

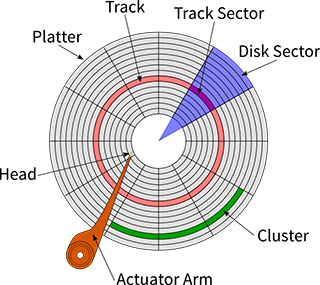

A disk is composed of stacked platters that spin/rotate while a head

assembly/actuator reads from one side of a platter at a time. The platter

has two faces, each face is called a head.

The platter itself is divided in concentric circles that are called tracks

or cylinders, the difference doesn’t really matter here. Those tracks are

also divided into smaller parts that are all the same size called sectors.

This is the sector that we’ve talked about when it’s applied to the hard

disk case.

If you know the right head, the right track, and the right sector then

you can pinpoint the data you want. However, most of today’s hard disk

have this abstracted and map sectors globally, so you can point directly

to a general address without having to know about the rest. Which is

also nifty because it can apply to other devices with sectors like SSD

or optical disks, not only hdd.

This is called LBA, Logical Block Addressing which is in contrast with

CHS, cylinder-head-sector addressing. LBA addresses can be translated

back and forth to CHS.

So when data is stored on the hard disk it’s usually stored on a bunch of sectors and whatever space is left on the sector is left as is, though some filesystem may optimize that space (but usually optimize blocks and not sectors).

Because data is stored on sectors and sectors are physical parts of a

disk that can have physical space between them, it takes time for the

head assembly/actuator piece to travel from one sector to another. The

average time it takes is called the seek time.

This time is quite big in computer time, from 5 to 10ms, it’s very slow.

As we’ve said some the optimizations done at higher level do take this

time in consideration and try to minimize it. Placement of files and

caching comes to mind.

SSD eliminates motor movement and rotation and so is faster and doesn’t have the same issues as with HDD and other medium.

With SSDs there are no moving parts, so a measurement of the seek time is only testing electronic circuits preparing a particular location on the memory in the storage device. Typical SSDs will have a seek time between 0.08 and 0.16 ms.

In sum, this is the layout of a hard disk and what it implies. It’s also nice to know that most physical medium have a hardware way to checksum, check the integrity and health of its own data. This is done through error-correcting code and bits. HDD, SSD, optical disks, etc. All have those.

The command that can show the physical sector size is the fdisk -l.

Now we can move to the connectors, the interface with the physical medium.

Connectors

Let’s focus on what those connectors are and what they do. When I say connector, I mean the low level commands to interact with the disk or other device - the hardware interface.

There are 3 different components or ideas that are the most important

here, the SCSI interface, the ATA interface, and the BIOS interface. All

of those are standards that could be implemented as ways of speaking with

the data storage, to make it do something useful and even configure it

in some cases.

The SCSI and ATA interfaces are to interact with the device directly,

we call those “direct access to controller”, while the BIOS, Basic

Input Output System, access to controller can be used as a middle man

to translate the communication with the actual device - Which as you

would guess is a bit slower but more convenient than the direct access.

On most Unix-like systems, the communication is done directly and doesn’t use the BIOS, which means SCSI and ATA are the main way of interacting with the storage devices and that there are specific drivers understanding how to do that.

Let’s note here that most direct access devices are equipped with read and/or write caches parameters. Remember that.

Wait, We know what’s a BIOS but what the hek are SCSI and ATA?

SCSI, skuzee or sexy (as the original creator hoped it would be pronounced

as), stands for Small Computer System Interface, it’s a set of “standards

for physically connecting and transferring data between computers and

peripheral devices”.

The standard defines a protocol and commands to interface and control

those peripheral devices.

Note here that we said peripheral devices and so this standard is

not limited to any specific data storage device, or data storage in

general. Though it’s commonly used for hard disk drives and tape drives,

it can be used for CD drives and scanners or anything else.

Simply said, it’s just a standard way of communication so that different

devices can communicate with each other. There are versions of the

standards with different speed increase over time.

Physically, the connector is the cable and the cable of the SCSI standards

have a distinct set of pins to send the data over.

What about ATA?

ATA stands for “AT Bus Attachment” or simply “AT attachment”.

The name originates from a standard first implemented in the IBM PC/AT,

where AT stands for “Advanced Technology”. Now it’s just kept as AT

Attachment to avoid trademark issues with IBM.

ATA has a long history of a series of iterative and incremental

updates. It was first a response to SCSI’s flaws. It has a different

connector/cable type, is cheaper, is faster, and has more features,

in theory.

One of the feature is the LBA which comes by default since v0 of the ATA. This LBA, logical block addressing, which we talked about earlier, is the physical address method that uses a single number instead of the cylinder-head-sector method. LBA became the new standard with backward compatibility to convert back and forth.

IDE, one of those version iteration names is sometimes mixed up with ATA.

In fact other names too get mixed up with it, like ATAPI, UATA, IDE,

etc. Because in fact they are near synonyms, they are referring to the

same thing.

What’s special about IDE disk, integrated disk electronics, is that they

have a logic board built into it. Actually ATA disks require a controller

which is built into the disk of modern systems. The controller issues

commands to the ATA disks over the ribbon cable, the channel.

IDE is not just the connector and interface, but it’s the fact that

you need a drive controller integrated into the drive as opposed to a

separate controller on or connected to the motherboard - like with SCSI.

The interface that an IDE uses is the ATA interface. This means that ATA

is limited to hard disk usage unlike SCSI which has a controller in the

motherboard so can be used with everything.

The ATA interface is the most popular disk interface these days, it’s

used everywhere.

Because it’s built into the disk ATA offers custom commands like hard disk password, the manipulation of disk specific parameters such as host protected area, the max address, the device configuration overlay, etc.

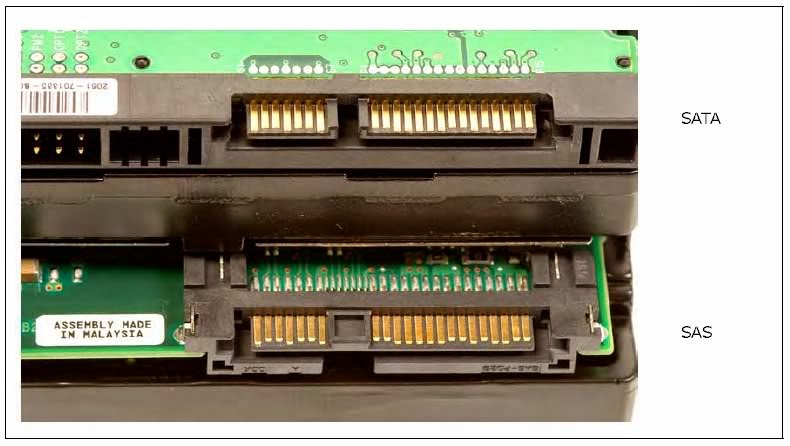

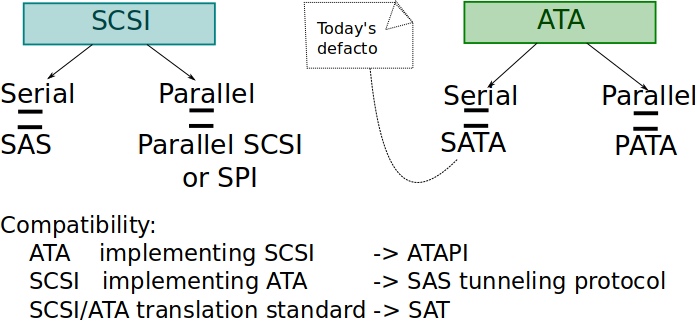

At some point ATA and SCSI started to bottleneck, they were getting slow.

Starting from the ATA-7 specification in 2003 something called serial

ATA, or SATA for short was introduced, at the same time the original

ATA was renamed parallel ATA or PATA for short.

The same happened with SCSI, with the serial attached SCSI or SAS for

short. Both of those offered many advantages while still being compatible

with their specific older interface.

Reduced cable size, faster speed, reliability, among others.

SATA is the defacto today for consumer devices such as desktop and laptops, 99% of the market share as reported in 2008.

So both ATA-like and SCSI-like interfaces sound very similar, they both

more or less do the same job, have direct memory access, feature command

queuing, have swappable connectors to allow to hot-plug the drives when

the system is on, have self-monitoring and analysis features such as

SMART, etc.

Now the question is: Can they work together, are they compatible?

And the answer is yes.

At first when ATA appeared they were cheaper but SCSI were already on

the market so the compromise was to implement in ATA the ATAPI, ATA

packet interface which would allow ATA devices to speak SCSI.

Then ATA got more popular than SCSI and so SCSI devices implemented

the ATA command pass-through feature, or serial ATA tunneling protocol,

which allowed ATA commands over SCSI bus.

SAS even used the same connection as SATA which allows a SATA drive to

be connected on a SAS backplanes/controllers, but not the reverse.

And then they finally put a standard in place for translation both way,

this standard is called the SCSI/ATA Translation (SAT).

So you can send ATA commands to SCSI devices such as CD-roms via the

ATAPI interface or SAT. Actually in practice ATAPI is only used for

devices other than hard disks.

So ok, that was a long overview of the hard disk world.

Now how do we access those on Unix, are there commands to configure,

set the hardward cache, etc., and get info about those drives.

A warning beforehand, you might crash your computer, loose data, or

not easily be able to recover if you execute some of those commands

improperly.

So, here are some:

fdiskto manipulate disks and show information about themhdparm -I /dev/sdato show and configure ATAscsiinfo -lsame for SCSI devicesscsitoolsbunch of tools for analysing and exploring scsi and atacamcontrolThe FreeBSD utility to manipulate driver of devicesatacontrolAlso FreeBSD utility to control ATA devicessmartctlto manipulate ATA devices that have the SMART featurevpddecodedmidecodebiosdecode- etc.

NB: SCSI can also work over the network over a protocol called

iSCSI.

NB: SCSI can also work over USB via UAS.

The Drivers

So those were the physical parts, and like most physical parts they need drivers so that the operating system can map/mount them and interact with them. How is it done on Linux and the BSDs? The big difference lies in the stuffs we’ve learned about just now, the SCSI and ATA.

On Linux there are two drivers, a deprecated one, the traditional IDE

driver which is used for many common SATA chipsets, and libata, the

newer ATA driver.

You can also optionally load (other than the driver for IDE) at the

software level support for BIOS interface we discussed earlier in

case it provides some specific manufacturer software such as RAID

(fakeraid/ataraid/dmraid).

What’s particular about libata is that it provides a SAT (SCSI/SATA

Translation) implementation, it sits inside the kernel well-tested SCSI

layer on Linux.

Each SATA port on Linux will appear as a SCSI bus.

SCSI as a lingua franca. SCSI is sometimes used as a lingua franca to internally represent commands for I/O devices, especially block devices, which do not directly support SCSI. For example, FreeBSD represents all block device commands internally as SCSI commands, and simply translates these to ATA commands when dispatching to ATA block devices. The SCSI/ATA Translation (SAT) standard defines nthe mapping between SCSI and ATA commands. It can likewise be mapped to NVMe. — A brief introduction to scsi

Ok, so what does that mean?

There’s a mid-level, that is the SCSI layer common to a bunch of other

lower operations that are translated to other SCSI-like services.

This layer, if built as a module would never need to be loaded as any

lower module would depend on it and load it. So usually it’s always

loaded and not a module.

Which means that those data storage device all use the SCSI

layer? Yes. And that means that if they want to use more specific

configurations they’ll have to bypass it to interact directly with the

device? More or less yes.

That also means that it affects the mapping of SCSI and ATA devices

under /dev.

Remember that a device is a gateway to a driver in the kernel that

controls the device and not the actual device itself.

So the SCSI and ATA disks are both mapped as /dev/sd* devices. sd

standing for SCSI device.

/dev/sda for the first disk, /dev/sdb for the second, /dev/sdc

for the third disk, etc.

And if we take a look under /proc/devices we can find out that those

are block devices (we’ll explain what that means later) with major

numbers 8 and 65 through 71, etc.

/dev/hdis used for the IDE subsystem./dev/srfor cdrom subsystem (iso9660).

There are more precise things in the devfs subsystem /dev/scsi and

you can get more details about the SCSIs by checking /proc/scsi.

NB: We call the endpoint that initiate the SCSI session a SCSI initiator and it connects to a SCSI target.

That’s enough about Linux, now what about BSDs?

Every BSD has a different way of implementing the drivers, and different

names but one thing in common is that there’s a separation of drivers and

mapping, that means a clear separation between ATA and SCSI and not a SAT

(SCSI/ATA Translation implementation). (EDIT: I might be wrong on this, see above quote from the “a brief introduction to scsi”)

We’ll take FreeBSD as an example.

The drivers that are interesting for us are the ad and da driver, the

ATA disk driver and the SCSI direct access driver.

Apart from those you have the ar driver for ATA RAID, the acd driver for

the ATAPI for cd or just cd for SCSI cdrom, the afd ATAPI for floppy,

the ast ATAPI for tape drive.

You can clearly see that the drivers don’t have a generic middle layer

like Linux but very separate ones.

So all IDE/SATA drives shows as /dev/ad* and all the SCSI drives and

USB mass storage as /dev/da*.

Another difference is that on FreeBSD block devices have been dropped

so all those devices are character devices.

A mention on block devices and the block layer

What are block devices, what’s the block layer, and why would FreeBSD drop it?

The idea behind all these, is that if there are a lot of requests to the

data device then it might not be able to handle the throughput and so a

queue/buffer/cache layer may need to be inserted in the middle so that

it is read before or written to before the real device.

This is the block layer that is found in the kernel and every block

device has a buffer in the block layer. This is what a block device is.

All block devices are viewed as a linear collection of blocks of the same

size, those blocks are the size of the cache entry, which is usually

the same as a filesystem block as we’ll see later, but is a different

cache than the filesystem cache.

This layer has some queuing and scheduling put in place too.

However, there are a lot of criticism about it.

- Some ATA devices already provide built-in hardware caching mechanism.

- Like all caches it’s stored in the kernel and add complexity to it.

- It may be unreliable as the kernel has to maintain efficiently the cache sometime reordering the requests, and also has to do some frequent housekeeping of the data structure.

- In case of crash the data might be lost and unrecoverable.

For all those reasons FreeBSD and others dropped support for cached/block disk devices.

The relevant command is: blockdev --getbsz /dev/sda to find out the

block size.

I haven’t found a way to flush the blocks directly on Linux because it’s

mixed up with the page cache too.

You can flush the filesystem page cache using sync but this is different

than the block buffer, however both page cache and buffers starting from

Linux 2.4 are joined (somehow, we’ll discuss page cache later on).

You have to do sync; echo 3 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches to drop them.

Yes this is a bit confusing.

So, we mentioned the way devices are mapped in /dev however there’s

the appended digits and characters we haven’t discussed, what are those.

Let’s talk about partitions and volumes.

Mid level - Partitions and volumes organisation

We mentioned partitions so let’s explain what those are and with those we can also insert the layers related to RAID, volumes, and encryption, as you’ll see those fit together in the same basket.

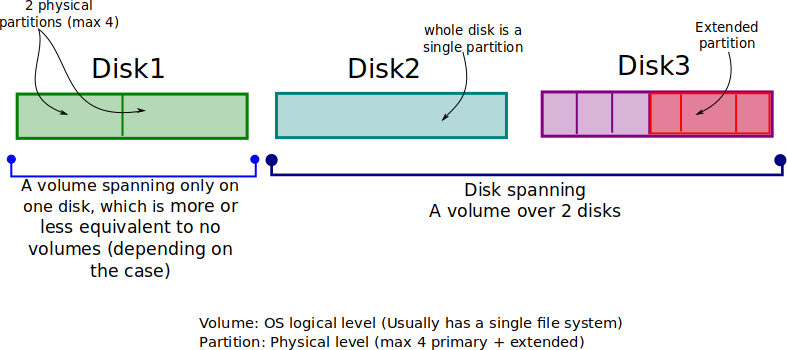

A partition is a way to slice/shred up a disk into multiple sections with different roles. There are many reasons for that, for example the separation of data or having multiple operating systems on the same disk. It’s practical because on Unix you can have separate partitions for different directories and those partitions don’t have to be mounted on the same disk. But what’s the difference between a partition and a volume, those terms sound similar and you might have heard of them in the same context however they shouldn’t be mixed.

A volume is a group of addressable sectors used for storage, addressable in the sense that they can be pointed to, thanks Mr.obvious. However, that means those sectors don’t have to be consecutive nor on the same disk. The operating system will see them as one big block, a volume. A volume can be a single disk, or many smaller disks into one, this is called disk spanning.

A partition on the other hand is a collection of consecutive sectors in

a volume. Now the limitation is that they live inside a volume and that

the sectors are consecutive.

The partition can be virtual if inside one of those volume or it can

be physical if directly on the disk. A physical partition can contain

a volume which can contain logical partitions.

Usually there can only be 4 main partitions on a disk, and a special

partition called an extended partition should be used to have more.

Check the podcast about booting on Unix for more info on that subject.

To sum it up a volume is what the OS considers as a bunch of addressable storage space, this can be many disks or a single disk, and a partition are the separate consecutive sectors that are part of those volumes or the physical disk.

You can have 3 partitions in one volume and that volume spanning over 2 disks. Usually a volume is synonym with one disk as setting up the other options is more tedious, we’ll discuss the implementation in a bit

Now how does the addressing works here?

There are many layers, remember when we mentioned the CHS

(cylinder-head-sector) way and the LBA (logical block address), now

you have to add to those the layer on top for the volume which is the

logical disk volume address, which basically starts at 0 for the start

of the sector of the volume and ends with it, remember that it doesn’t

have to be the start of the disk.

Other than that you have to add the same thing for the logical partition,

a way to point to sectors inside, thus there is the logical volume

partition address.

That’s a lot of blocks stacking up.

As we said normally the volume is the physical disk itself but to have the spanning over multiple disks or chunks of disks you have to have a software implementation or a hardware one. This could consist of a specific volume management driver or of RAID. Let’s discuss some software implementations.

On Linux for instance, to make those all work, it uses a layer called

the device mapper, a framework provided by the kernel to map physical

block devices into virtual block devices that can be used by those

“volume-like” modules.

It’s a transition module in the middle of the block layer and the

volume-handling layer.

It can also be used for disk encryption (dm-crypt).

This device mapper behavior is also present in some BSDs such as NetBSD

and DragonFly BSD.

On Linux there are two implementations of the volume management, LVM (logical volume management) and MD.

LVM calls the volume a disk group or volume group, Disks in the volume group are divided into physical extents, equal size containers. A logical volume is made up of logical extents, and there is a mapping between each logical extent and the physical extent.

What about RAID, the redundant array of inexpensive disk.

We consider it in the same category as volume handling as it manages

multiple disks, sometimes as one, sometimes as replication, sometimes

as error correcting.

RAID 0 is like disk spanning of volumes, it spreads the data over multiple

disks in chunks.

- RAID 1 is pure mirroring.

- RAID 2 adds some error correcting codes.

- RAID 3 adds a disk that calculates the parity of the last bytes.

- RAID 4 is like RAID level 3 but using block sized chunks.

- RAID 5 does the same as RAID 3 but alternating the parity check from one disk to another.

The mapping of the devices in /dev changes according to what we’ve discussed, apart from the SCSI and SATA we mentioned earlier. It adds volumes and partitions to the mix. (Though device mapper wrappers, virtual block devices, are mapped separately, for example on Linux in /dev/mapper/whatevermappingname)

On Linux partitions are represented by additional numbers added. For example, the first SCSI disk is /dev/sda and the first partition on it /dev/sda1, second partition /dev/sda2. That is regardless if it’s a partition on an extended partition like GPT or one of the 4 main partitions.

On FreeBSD it’s a bit similar.

However, the naming differs, the 4 main primary partitions are called

“slices”, then has logical “partitions” inside the slice.

The drive number is also, like on Linux, define by adding a digit at the

end of the device name (instead of a letter): /dev/ad0 is the first

SATA drive, /dev/ad1 the second, etc.

The slices (4 primary partitions) are defined by adding an “s1”, “s2”,

“s3”, “s4” after the drive in question.

So for instance for the first slice of the first SATA disk you would have

/dev/ad0s1 and for the second slice /dev/ad0s2.

As for the partitions inside the slice, it’s done by adding a letter:

/dev/ad0s1a, /dev/ad0s1b.

Usually on FreeBSD those partitions are standardly mounted on specific

directories, such as “a” being /, “b” being the swap, “c” overlaps

all the other partitions on the disk, “d” covers the whole disk entirely.

What does mounting mean?

On Unix everything is represented under a root directory, even the disks

themselves and so you need to have a sort of access point that says this

directory points to this device.

In simple terms that’s what a mount point is.

For example, you mount /dev/sda3 as an ext2 filesystem on the mount point

/tmp and whenever you write data to /tmp it’ll be on /dev/sda3.

There are many ways to mount a device, you can use fstab, you can

manually mount the partition, you can dynamically mount it, etc. But

I won’t go into more details.

How does the OS know where to find them?

What’s a partitions

A partition is defined inside the parent volume/disk partition table,

be it a DOS/MBR partition or a GPT (extended) partition (check the

podcast about booting for more details, or just read up online).

It’s a fixed size structure that contains metadata about what’s in there,

it can say “here is an LVM partition” or “here is some boot code” or

“here is an ext4 filesystem”.

One of the entry in that structure does just that, it’s the partition

type a Byte specifying the partition ID, which is the type of filesystem

or object present on this partition.

For example:

0x83— linux0x85— linux extended0x8e— LVM0xa5— freebsd0xa6— openbsd0xa8— max osxoxa9— netbsd0xee— efi gpt partition0xef— efi system partition

There’s a list in the show note (partition_type).

Other parts of the structure are the size of the partition, where it starts and where it ends. But what’s actually inside the partition we are mounting?

Usually there’s the filesystem. In the first few sectors of the partition the filesystem stores its metadata, its label, its paging area, the file system structure, the control block with ownership and data location, the free space mapping, and a lot of specific filesystem components. Here are a bunch of useful commands:

~ > sudo blkid

/dev/sda1: PARTLABEL="BIOS boot partition" PARTUUID="093c568a-be66-4475-99b6-a70dc67f635d"

/dev/sda2: UUID="78b19097-1d52-4c9f-b076-813bfff87118" TYPE="ext4" PARTLABEL="Linux filesystem" PARTUUID="5e2787ff-023d-4768-aeda-c268b5909c5b" ~ > lsblk

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINT

sda 8:0 0 465.8G 0 disk

├─sda1 8:1 0 1M 0 part

└─sda2 8:2 0 465.8G 0 part /

sr0 11:0 1 1024M 0 rom ~ > sudo fdisk -l

Disk /dev/sda: 465.8 GiB, 500107862016 bytes, 976773168 sectors

Units: sectors of 1 * 512 = 512 bytes

Sector size (logical/physical): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

I/O size (minimum/optimal): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

Disklabel type: gpt

Disk identifier: 58570BC8-A049-4505-BC69-74B186F748C2

Device Start End Sectors Size Type

/dev/sda1 2048 4095 2048 1M BIOS boot

/dev/sda2 4096 976773134 976769039 465.8G Linux filesystem ~ > lsmod | grep ata

Module Size Used by

libata 208896 2 ahci,libahci

scsi_mod 155648 3 sd_mod,libata,sr_modOk, now what exactly is a filesystem, what does it do, what’s particular about it, how can it be implemented, and what are all this metadata for.

High Level

A big overview of FS

As we said the partitions are defined by their type, one of those type is the file system type.

The partition, the isolated storage segment, is loaded and interpreted as a filesystem. A file system is the bulk of this episode, without it nothing makes sense, without it, it would be data scattered around with no specific meaning attached to it. The file system is the way the OS store, update, and retrieve the data.

Ah that sounds repetitive, we’ve already said that it seems. But this time it stores the data in a hierarchy of files and directories. It’s the file system that create the structure around files and use data so that the OS knows where to find them and what they represent. It’s a “structured data representations and a set of metadata describing the stored data”.

We gave the metaphor in the introduction of this podcast about the filing system that some banks have, well this is the job of the file system. It keeps track of what is what, their name, where they are, who has access to them, it organises them, keeps the office tidy, etc. And when you ask it where something is then it has a procedure in place to be able to find it as fast as possible. To do all that the file system needs an internal data structure and organisation: The metadata and caching.

It has two structures in place, one in memory and one on disk, a temporary and permanent one. Let’s talk generically and then discuss the differences between implementation of file systems in the Unix world.

First, the layer just under the file system is the block layer,

or whatever replaces it, thus the file system operates on blocks and

not on sectors. Those blocks range from 1 to 128 sectors (512B-64KB).

The file system stores files on those blocks, usually at the start of

the block and taking it entirely, even if the file doesn’t fill it all.

(Just like sectors space is wasted)

There are some exception to this where the file system optimizes that

wasted space, this is called block suballocation. And the wasted space

phenomena is called internal fragmentation.

The last few things I mentioned mean two things, that the file system

should keep track of which block is used and unused and to keep track

of what is on which blocks.

Both this information is stored in what we call the superblock or

volume descriptor.

It contains all the important metadata required to use this file system,

its type, size, status, and more importantly information about where

other metadata structures are such as the free space mapping structure,

and the structure that represents the files used on which blocks.

Without the superblock the file system is useless, it cannot be mounted

and cannot be used.

Those are the permanent structures.

The tracking of free space could be simply implemented as a

bitmap/bit-vector, every bit position representing the position of the

block in the block data of the filesystem. Or it could be a linked list,

or anything, this depends on the implementation.

The second structure is the inode table, a table containing all the

inodes.

The inodes or vnode or other kind of similar implementations names

is a structure that has a number (an id) and other data that can help

pinpoint the files on the disk and letting the OS access the files.

It contains things such as the file size, the device id of the device

containing the file, some permission related metadata, some timestamp

metadata, a count of the number of hard links pointing to that file,

and more importantly here: “Pointers to the disk blocks that store the

file’s contents”, the inode pointer structure.

There are usually two inode numbers that are recurrent on most Unix

systems, inode 1 is used as a “bad blocks inode”, and inode 2 is used

as the root directory inode.

For example on Linux /sys and /proc which are not on the disk have

the inode 1.

One thing to note is that if the file system runs out of inodes then it

is considered full, even though the disk might not be.

A block in itself could be smaller than the file size, that means a file will own multiple blocks to store its content. In its inode it has a list of pointers to the disk blocks. But when a file is created how do we choose which blocks to give to a file, how do we do space management. Well, obviously this is file system dependent.

Common ways to allocate the blocks are the first block found, or the last

block found, or the best fit, or the worst fit. You can mix those around.

Usually the worst first fit is the best algorithm as it reduces the

amount of external fragmentation.

Fragmentation is when unused space or single files are not contiguous

on the disk, the file blocks are scattered around.

This happens when a program allocates blocks and then frees blocks in

the middle and then the memory allocator uses this free block to store

the data but the data doesn’t fit in one block and thus it’s allocated

to another block further away. Another case when it happens is when

a file grows in size and doesn’t fit in the space allocated already,

it has to allocate a new block that isn’t contiguous.

With Unix file system fragmentation isn’t that big of an issue but with

other file systems it might as the head/actuator will be moving around

the disk too much and slowing reading speed.

On Unix disk reads are cached, and even has read-ahead, which buffers

the next block intelligently. Moreover, the position of the disk head is

irrelevant as Unix is a multi-tasking OS and multiple users will already

be reading all over the disk.

Overall disk fragmentation is a sign of a bad implementation of block

allocation.

Ok, so that’s how allocating blocks work but how can it be stored, all

those related blocks together in the inode or whatever structure used

to store the file information.

It could be a contiguous preallocated array of blocks, it could be a

linked list of pointers to next blocks, etc.

Most Unix file system use a combination of direct and indirect block

pointers, for example allocated in this fashion: Allowing 12 direct

block pointers and 3 indirect block pointers, single, double, triple.

A direct block pointer is a pointer to a block that the file has data

into, an indirect one is a pointer that points to another direct or

indirect block pointer.

The combination of those means that the file can grow as it needs.

In the past, the structure may have consisted of eleven or thirteen pointers, but most modern file systems use fifteen pointers. These pointers consist of (assuming 15 pointers in the inode):

Twelve pointers that directly point to blocks of the file’s data (direct pointers)

One singly indirect pointer (a pointer that points to a block of pointers that then point to blocks of the file’s data)

One doubly indirect pointer (a pointer that points to a block of pointers that point to other blocks of pointers that then point to blocks of the file’s data)

One triply indirect pointer (a pointer that points to a block of pointers that point to other blocks of pointers that point to other blocks of pointers that then point to blocks of the file’s data)

What about the in-memory structures we mentioned.

The kernel keeps a global file table, it keeps track of the byte offset

where the user’s next read/write will start, the access rights, etc.

The in-memory structures can also have a process file descriptor table

keeping track, in every process, of the files taht are currently opened.

It also has a page cache, a copy or partial copy of file content,

sometimes at the virtual file system level.

In some cases it unifies it with the buffer cache into a two-page cache,

both the hard disk page size and file system block size.

The difference is that buffers (block layer) are associated with a

specific block device and its metadata while the page cache contains

parked file data.

That is, the buffers remember what’s in directories, what file permissions

are, and keep track of what memory is being written from or read to for

a particular block device. The cache only contains the contents of the

files themselves.

Buffer = Metadata; Cache = Data;

The page cache caches pages of files to optimize file I/O. The buffer

cache caches disk blocks to optimize block I/O.

This is confusing as the block layer caches writes to disk, the page

cache caches pages of files, and the buffer caches blocks and metadata

about the filesystem.

It has confused me too and I’m not sure the differences are clear here.

The memory structure can also have cached directory information, which

is very important, the dentry.

FS Examples

What can differ from one file system to another.

The block size, the caching algorithm, the

block-allocation/space-management algorithm, how it stores the metadata

about files and what’s in that metadata, the speed at which the data is

fetch, if it has some specific features.

Bigger block size will mean improve disk I/O performance when using large

files but when using small files it will result in a lot of wasted space

if suballocation is not used.

For example as of 2015 (wikipedia), block suballocation is most widely

used with Btrfs and FreeBSD UFS2.

Another example, Ext2 space management algorithm tries to find 8 free

data blocks before allocating and doesn’t allow two files to allocate

at the same time.

An interesting allocation is the data block deduplication, which will

consider identical block as the same block and not reallocate it.

The HAMMER file system implements this.

A file system can have some extra integrity mechanisms, if the power

is cut before the data is written to disk or if there’s a media failure

there should be a way to recover.

Some file systems offer some damage correction, fault-tolerance,

structures and features such as checksums, recovery, rollbacks and

journaling.

The Ext2 file system, for instance, has integrity check.

Ext3 has journaling and ReiserFS too.

Journaling meaning that the file system maintains a journal/log of what

is currently happening on the file system, thus can traceback events in

case of crash.

Some file systems have some limitations in size, what it allows in its filenames, etc.

Some file systems have a snapshot feature, allowing to backup and rollback.

For example ZFS, HAMMER fs, and Btrfs implement this snapshot feature.

Some file systems allow pooling, sub-filesystem or sub-volume managed by

the file system itself, yet another splitting. Though it could be said

that it’s and implementation of a file system and a volume manager in

the same software.

ZFS and Btrfs also have those.

There are file systems optimized for specific devices and usages.

For example there are file systems optimized for flash memory, solid

state media, for CDROM and optical discs, others for distributed systems,

others for network, others for encryption, etc.

Some commands that can be interesting here are the mkfs and newfs

and fsck for checking a file system integrity.

There’s also GNU parted that can be used to create file system.

NB about 32 bit limitation

It’s common parlance that on 32-bit operating system file systems have a certain limitation for their file size. This is actually not a limitation from the file system, not from POSIX, but rather indirectly from ISO/ANSI C. If you’ve listened to the podcast about bits and words then you would guess what the issue is.

“The lseek() file offset is defined as off_t, there’s nothing in a

32-bit POSIX compliant system to stops it to typedef’in it as a 64-bit

signed “long long”, same for a bunch of function like fsetpos and

fgetpos, however the problem lies with ISO/ANSI C fseek and ftell

functions which use a “long” for the offset instead of fpos_t. This

limits the size of a file to 2GB.”

“Thus, it is ISO/ANSI C compatibility that is necessarily broken for file systems that support bigger-than-2GB files with 32-bit longs – something that applies even to non-POSIX file systems that claim compatibility with ISO/ANSI C. I’m sure you all can think of at least two, but that’s a discussion for the advocacy lists.”

A bit about history and the origin of Unix FS

The original ideas about file systems haven’t changed much since the early days. The first Unix file systems were referred to as FS, they had boot block, superblock, a clump of inodes, and the data blocks. Which we also have today, however today we have much more efficient structures.

The ideas weren’t all new, as with everything UNIX, it was inspired

by MULTICS and other operating systems that had those kinds of similar

structures. What was new was the simplicity over functionality.

This simple file system was improved later by the BSD guys to reduce the

disk head/actuator movements, it broke the disk into smaller chunks/groups

and each having its own inodes and data blocks. The cylinder clusters

and bit-map free lists.

Till today most file systems have similar commonalities such as dividing

the disk in blocks, using inodes for files, have a directory structure,

use the first block of each volume for bootstrap, use an inode table,

have a superblock aka volume descriptor, a block pointer scheme, etc.

There’s not much to say about the original history of file systems,

however there’s one part that is important for the next topic: Having

different types of file systems together.

VFS & POSIX I/O layer

The virtual file system is an abstraction layer that interfaces between the user and the file system in use, its role is to give the same interface whatever the file system in use. So the file system is within this layer. More precisely “The VFS provides the abstraction layer, separating the POSIX API from the details of how a particular file system implements that behavior.” This means Unix-like OS that have this kind of interface support different type of file systems.

Generically those are layers that allow an operating system to access

a file system via a common interface, a file system interface.

This is called the common file model.

There are many implementations such as FUSE, LUFS, VFS, which is the

most used name for it on Unix-like systems (even though they might not

be the same).

Where does the concept of VFS come from?

Virtual file system mechanism on Unix-like system was introduced by Sun

microsystems in SunOS 2.0 in 1985.

Sun introduced a way to access the local UFS file system and the remote

NFS transparently from the same usual system calls.

Other vendors that were implementing the NFS of Sun had to also implement

this layer.

Other file systems could also be plugged in this layer to add support

for them, for instance MS-DOS FAT was developed for SunOS.

Soon enough this lead to widespread implementation of the same mechanism,

the SunOS implementation was the basis of the VFS mechanism in System V

Release 4 and later implemented in 4.4BSD and derivatives.

In 1993, the ext2 file system was added to Linux instead of the MINIX-like

implementation to allow support for different kind of file systems.

But how does the VFS work, how does it know which file system is present.

It all has to do with superblocks, it reads it, knows what kind of file system it’s dealing with, and map it to its internal memory structure of VFS superblocks. The real file system stays as a driver or built-in the kernel. Thus, every mounted file system is represented by a VFS superblock, which contains the following and more: The device that contains that file system, the partition, etc. The file system type it is. Inode pointers, those point to the first inode in the file system and the inode of the directory it’s currently mounted on. The block size of this file system. The superblock operation, a translation table/map (operations vector) of routines used to interact with the file system. The VFS also has its own inodes, the VFS inodes which are built from information of the underlying file system inodes.

The system processes accessing files and directories do it through

this layer.

And if those inodes are accessed repeatedly they are kept in the inode

cache of the VFS for quick access so that it doesn’t have to be fetched

again.

This is yet another layer of cache other than the built-in one in the disk

and the block buffer layer (or whatever abstracts is like map-device).

Now you can say that here it’s the VFS that inserts data in the

buffer/block layer.

The VFS also keeps a cache of directory lookups so that the inodes for

frequently used directories can quickly be found, the dentries cache.

As the name implies, the VFS is virtual and so those structures and

caches are kept in memory and not permanently.

So this is the VFS from the side of the file system, what does it look

like from the side of the user?

In short, it provides the basic POSIX file I/O functions.

When a system call is issued it passes through the common interface

provided by the VFS, is mapped via the VFS superblock and interpreted,

buffered through the block layer if any and then goes down the pipeline.

There are many system call supported by the VFS such as:

Mount(), umount()

Chroot()

Chdir(), fchdir(), getcwd()

Mkdir(), rmdir()

Getdents(), link(), unlink(), rename()

Readlink(), symlink()

Chown(), fchown(), lchown()

Chmod(), fchmod(), utime()

Stat(), fstat(), lstat(), acess()

Open(), close(), creat(), umask()

Dup(), dup2(), fcntl()

Select(), poll()

Truncate(), ftruncate()

Lseek()

Read(), write(), readv(), writev()POSIX I/O

User-space programs interact with the file system API, the POSIX I/O. Whenever they write data, read from files, manage directories, mount devices, change metadata on files, etc.

This is the logical layer on top of it all, the one that interacts with the user applications directly. It manages the open file table entries, and per-process file descriptors. It also provides security mechanism and protection, such as access control list.

For example on the open() system call the file descriptor table

allocates a file descriptor which points to an entry in the global

file table which contains all the I/O byte offset related information,

where we are currently reading in the file. This global file table has a

pointer that points to the proper inode number in the inode table. And

then it goes down to the layer of the VFS to the file handling on the

related file system.

The POSIX I/O is great but sometimes criticized for what it’s good at.

Because it has to pass through so many checks of metadata on multiple

layers and the page cache, it sometimes isn’t the best alternative when

real time I/O is in need.

Although its strong point is consistency and portability.

I’ve linked an article in the show notes titled “What’s So Bad About

POSIX I/O?” it lists some reasons why for high performance I/O it

would not be that good. However, for higher speed would break a lot

of consistency.

MANAGEMENT, COMMANDS, & FORENSIC

If you want to know more about your data storage you’ll have to dig into the world of forensic. I’ve linked a book in the show notes called “File System Forensic Analysis”, it’s a great resource.

There are a bunch of open source tools that can be used to retrieve

information from a disk, for example the sleuthkit, which is a collection

of tools for forensic analysis.

Other useful tools such as photorec can be used in case of data

corruption to retrieve the files on a disk.

But as with anything that messes with your data storage be sure to do

backups before playing with them.

Conclusion

So this is it, you should now have a big gross overview of the whole

data storage architecture on Unix.

What you have to remember is that at every layer there’s an encapsulation

and abstraction of the data passing through.

It all represents abstracted access to data.

From the disk to the drivers, to the block layer, to the file system,

to the virtual file system, to the POSIX file I/O.

As usual if you have something to add to the podcast or if you want to correct a mistake then comment on the forums and contribute to the discussion.

Music

Mosquito by Pk jazz Collective http://store.southerncitylab.net/track/mosquito.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IO_stack_of_the_Linux_kernel.svg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File_system

- https://help.ubuntu.com/community/LinuxFilesystemsExplained

- Non-POSIX File Systems

- http://linuxfinances.info/info/fs.html

- http://www.ufsexplorer.com/und_fs.php

- http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~410-s07/lectures/L27_Filesystem.pdf

- https://jkmaterials.yolasite.com/resources/materials/UNIX/UNIX_INTERNALS/UISVE/UNIT-III.pdf

- http://www.netbsd.org/docs/internals/en/netbsd-internals.html#chap-file-system

- http://www.porcupine.org/forensics/forensic-discovery/chapter3.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cylinder-head-sector

- http://www.yolinux.com/TUTORIALS/LinuxTutorialSCSI.html

- A brief introduction to scsi

- http://www.tldp.org/HOWTO/html_single/SCSI-2.4-HOWTO/#intro

- https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/144561/in-what-sense-does-sata-talk-scsi-how-much-is-shared-between-scsi-and-ata

- https://www.kernel.org/doc/htmldocs/libata/

- https://www.linuxquestions.org/questions/linux-general-1/sata-vs-scsi-for-a-server-387308-print/

- https://www.freebsd.org/doc/handbook/geom-glabel.html

- https://www.cyberciti.biz/faq/freebsd-hard-disk-information/

- https://www.freebsd.org/cgi/man.cgi?query=smartctl&manpath=FreeBSD+9.0-RELEASE+and+Ports&format=html

- http://nixdoc.net/man-pages/FreeBSD/ata.4.html

- https://www.freebsd.org/cgi/man.cgi?query=da&sektion=4

- http://www.webopedia.com/DidYouKnow/Computer_Science/sas_sata.asp

- https://insidehpc.com/2006/04/what-is-the-difference-between-scsi-and-ata/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SCSI

- http://linuxmafia.com/faq/Hardware/sata.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serial_Attached_SCSI

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parallel_ATA

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serial_ATA

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industry_Standard_Architecture

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logical_block_addressing

- https://www.freebsd.org/doc/en/books/arch-handbook/driverbasics-block.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Device_mapper

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disk_partitioning

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partition_type

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partition_table

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Master_boot_record

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BSD_disklabel

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/LVM#Introduction

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Software_RAID_and_LVM

- http://www.tldp.org/HOWTO/Linux+FreeBSD-2.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logical_Volume_Manager_(Linux)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_file_system

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fragmentation_(computing)#Internal_fragmentation

- http://www.tldp.org/LDP/lki/lki-3.html

- http://learnlinuxconcepts.blogspot.com/2014/10/the-virtual-filesystem.html

- http://www.tldp.org/LDP/sag/html/buffer-cache.html

- https://www.ibm.com/developerworks/library/l-virtual-filesystem-switch/index.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_scrubbing

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copy-on-write

- http://www.goop.org/~jeremy/userfs/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File_descriptor

- http://linuxfinances.info/info/defrag.html

- http://www.tldp.org/LDP/tlk/fs/filesystem.html

- http://www.tldp.org/LDP/sag/html/filesystems.html

- http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man5/filesystems.5.html

- http://edusagar.com/articles/view/22/Unix-File-System-internals

- http://www.cs.pomona.edu/~markk/filesystems/bsd.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ext2

- http://e2fsprogs.sourceforge.net/ext2intro.html

- http://teaching.csse.uwa.edu.au/units/CITS2002/fs-ext2/ext2fs_1.html

- http://xpt.sourceforge.net/techdocs/nix/general/gnl10-SystemMaintain/ar01s06.html

- http://perl.plover.com/yak/ext2fs/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Log-structured_File_System_(BSD)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Procfs

- http://www.tldp.org/LDP/intro-linux/html/sect_03_01.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_file_systems

- http://www.shub-internet.org/brad/FreeBSD/postmark.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disk_sector

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_disk_drive_performance_characteristics#Seek_time

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_suballocation

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inode_pointer_structure

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inode

- https://dlorch.github.io/hammer-linux/files/hammer-lorch.pdf

- http://www.osdevcon.org/2009/slides/zfs_internals_uli_graef.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ReiserFS

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HAMMER

- https://www.dragonflybsd.org/hammer/

- https://www.princeton.edu/~unix/Solaris/troubleshoot/zfs.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/QNX4FS

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XFS

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ZFS

- scsitools-gui

- <Installation: https://docs.freebsd.org/doc/7.4-RELEASE/usr/share/doc/faq/disks.html>

- http://www.tutorialspoint.com/unix/pdf/unix-file-system.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PhotoRec

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GNU_Parted

- http://freecode.com/projects/fstransform

- http://www.cis.upenn.edu/~bcpierce/unison/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix_File_System

- http://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~remzi/OSTEP/file-implementation.pdf

- http://www.scylladb.com/2017/10/05/io-access-methods-scylla/

- https://www.nextplatform.com/2017/09/11/whats-bad-posix-io/

- http://www.campus64.com/digital_learning/data/cyber_forensics_essentials/info_file_system_forensic_analysis.pdf

If you want to have a more in depth discussion I'm always available by email or irc.

We can discuss and argue about what you like and dislike, about new ideas to consider, opinions, etc..

If you don't feel like "having a discussion" or are intimidated by emails

then you can simply say something small in the comment sections below

and/or share it with your friends.